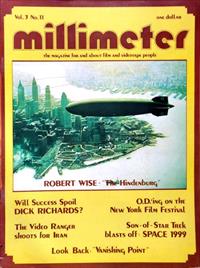

Press

Son-of-STAR TREK Blasts Off!

by Mark Carducci

Millimeter Magazine ("the magazine for and about film and videotape people"), Vol 3 Issue 11; by Mark Carducci p16-18 (1975)

scanned by Paulo Jorge Morgado

The existence of a highly touted, filmed-for-syndication television series called Space: 1999 is, by now, no secret to most of us. The program comes as Manna from heaven to thousands of Star Trek-starved science-fiction fans, not to mention a welcome relief to the average viewer weary of this season's all-too-numerous and all-too-trite police crap and medical mindlessness. Space: 1999 hails from Britannia, where it was lensed under the experienced auspices of Gerry and Sylvia Anderson's Century 21 productions. The husband and wife producing team are no strangers to sci-fi, having to their credit a long list of hit genre series which includes Fireball XL5, Captain Scarlet and more currently UFO. The Anderson's have shrewdly calculated the existence of a void in televisionland, precipitated by the networks' axing of Star Trek, and they wisely intend to fill it. Whether they succeed or not remains to be seen, but either way, they deserve applauds for their ambitious attempt.

The producers have borrowed some of Star Trek's more appealing aspects and utilized them to excellent advantage The series will feature a number of continuing characters, as Star Trek did, presided over by Martin Landau and Barbara Bain, the male and female commanders of a lunar colony. As the Enterprise was able to "'seek out new life and new civilizations," so too will the cast of Space: 1999, when the moon breaks out of the Earth's orbit, sending the four hundred-odd inhabitants of Moonbase Alpha hurtling on an endless journey through uncharted space.

Obviously, special effects of a very special nature will play an important role in each and every episode of Space: 1999. In order to obtain them, the Anderson's employed a full-time crew equal to the task, all laboring under the capable guidance of chief effects technician Brian Johnson. I had the pleasure of observing Brian and his merry band of effects men on the set, during which time I was told everything about Space: 1999 that I wasn't afraid to ask.

Upon first meeting Brian Johnson I knew very little about him, other than the fact that he had worked for Stanley Kubrick as one of several hundred effects men on 2001: A Space Odyssey. It seems a fruitful topic with which to begin our conversation, so I question Brian on what it was like to call Stanley Kubrick his boss.

"Stanley, as has often been said is a genius, but he is capable of being extremely eccentric. For six months he wandered around the set telling everyone about his next film - a feature length film featuring doIls. Of course, he abandoned the idea, but at the lime he was totally obsessed by it. Working for him for, three years made me realise he's sort of a committee organiser. He assembles huge groups of people and then sits down with all of them to discuss every possible way of doing something. Stanley listens to everyone and then makes his decision. He picks your brain, something he is very good at. Occasionally, though, his methods would cause undue tension in the crew. He would assign the same effect to several different men. That tended to put an unpleasant edge on things."

I wonder aloud whether it is in fact true that Kubrick designed most of 2001's visuals himself. "No, not really. Stanley simply made the proper use of a great many talented people. If credit for the visuals could go to one man alone, and it can't, that man would be Douglas Trumbull. Doug was responsible for a great deal. But really, it was all of us working together."

Brian and I walk towards one of several work rooms where the actual construction of miniature terrains and spacecraft takes place. All this activity is centered in the English countryside, at Bray Studios, which from its roadside gates looks alarmingly like a rural farm. Once upon a time, Bray was the home of Hammer Films, producer of many a Technicolor Dracula and Frankenstein Film, but today its confines hold only Brian, his crew, myself and a handful of carpenters hammering up the sets for the film version of The Rocky Horror Show

Brian enters one of the workrooms, and I follow him inside. The studio interior is cavernous, but there is little room to walk about. Tables crowded to overflowing with plastic model kits of planes and rockets line every wall. Half a dozen expert model-makers sit at these tables, painstakingly gluing tiny fins and minute rocket exhausts to a four-foot-long spaceship. Brian explains the process: "We use small parts from kits to give the models greater detail. In that way we can get as close to the models with the cameras as we like and maintain believability

." One space vehicle in particular catches my fancy, and I ask Brian about it, requesting he pose with it for a photo or two. "It's called an Eagle, and it's kind of a transportation/warship. I designed it with a modular approach. Do you mind if I put it down, though. It's quite heavy."

He tells me that the-copper tubing used in the Eagle's frame causes the "'miniature" to weigh in at close to eighty pounds! Brian winces and takes a moment to catch his breath. I apologise. (Naturally the picture when developed is out of focus.)

Elsewhere at Bray, on one of the small but versatile effects stages, Brian's crew is about to film the explosion on an asteroid. As we make a beeline for the location, Man informs me as to how he entered the field of movie-making. "I started as a camera assistant for a small film company, where I met Les Bowie, one of our top effects men, and he hired me as an operator' on The Day the Earth caught Fire. I got rather keen on effects after that and went on to do sci-fi and horror stuff for Hammer. Then I did thirteen Thunderbirds episodes for Gerry Anderson. After these I got a call from Wally Gentleman to come and work on 2001. I learned a great deal in those three years."

We are now standing on the soundstage. Brian's crew goes briskly about their business and Brian leaves me for a time to check their progress. I do my best to stay out of everybody's way, no easy task. As I watch them running about, all keyed up and shouting friendly obscenities at one another, I am reminded of children playing with their toys. Unlike many industry technicians, these men seem truly in love with their work. They've found their niche, a place where they can create in a world of fantasy and get a salary in the bargain. Nick Allder, Brian's demolition expert, shouts at the top of his lungs across the set. "Almost ready for the bang, Brian

." Brian spots me and motions for me to step behind him, out of harm's way.

"As you can see, the camera is mounted on the floor, shooting straight up. The asteroid, a plaster model, is suspended about fifteen feet above it, wired with an explosive charge to a detonator which Nick is holding. We'll be filming at one hundred and twenty frames per second to slow down the action. In the script a ship has deposited a couple of nuclear charges on the asteroid, which is on a collision course for the moon.

"It nearly collides with the moon before the charges destroy it. The fly-by of the spaceship has already been filmed on the raw stock in the camera. Except for the rocket, the footage is unexposed. But, in effect, by double-exposing the film we cut down a great deal on grain and get to see our results much sooner, as there is no waiting time while the lab prints in separate elements optically. One episode called for a mass exodus of fourteen Eagles from Alpha base. At the time we had only one, so we double exposed the other thirteen of them, plus a moonscape. That meant fifteen separate passes of the same negative through the camera. Actually, it worked quite well.

"

"We're ready here. Brian

."

"Right. Okay. Quiet everybody

." Nick Allder awaits Brian's countdown. The high speed Mitchell is running. "Five. Four. Three. Two. One

."

Nick depresses the plunger of the detonator and with an ear-splitting crack the asteroid bursts into a thousand pieces, tossing flaming bits of explosive jelly and plaster in high arcs all around the stage. I see the headlines: "'Reporter Incinerated in Special Effects Accident." Nick has overestimated the amount of powder and the asteroid is now ablaze, swinging wildly on its wires. While I clear my ears and brush debris from my jacket, two assistants ascend ladders to reach the asteroid and extinguish it. Brian coolly informs me that the shot is no good. "Too much flame. We'll have to do it again

." I nod blankly, recovering from the shock. Judging from everyone's sour expression, nobody is particularly thrilled about this. For a moment there are frowns all around. Brian calls a break for lunch and the frowns disappear. Slightly. As we leave the set, Brian apologizes for not being able to introduce me to Martin Landau or Barbara Bain. "They're on the stages at Pinewood

," he says, "shooting the live action. One stage is kept solely for alien landscapes and moon-surfaces, and another houses the interior of Alpha base. All the sets were designed by Keith Wilson, who adopted my Eagle modular concept to the entire base. It's all built in sections - door sections, corridor sections, it all fits together. This makes it possible to rearrange the sets literally hundreds of ways."

I dine with Brian and his crew at a nearby pub. The food is surprisingly good, and by the time I must make my exit I am comfortably fortified against the British damp. We finish lunch, and Brian drives me to my train. I bid him thanks and farewell, asking him one last question. "Will today's asteroid fiasco upset your schedule?"

"I hope not. We do have a lot of pressure on us. In the first episode alone there are over one-hundred and seventy-five effects cuts. We must average three or four useable shots per day, so it can get pretty hectic. My biggest enemy is always time."

Post Script: As of this writing all episodes of Space: 1999 have been completed and sold to local television stations in over one hundred and forty markets. It is impossible to predict whether the series will be with us until 1999, or even until next season, but the high quality of its effects work will warrant the watching of an episode or two, at least. Visually, Space: 1999 is nothing less than a 2001 for the tube. As television science fiction goes, it is highly entertaining space.

Captioned Photos