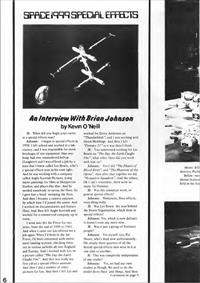

Brian Johnson interview

Just Imagine Vol 1 No 1 May-June 1975 p6. It was reprinted on a single page in Vol 2 No 1, winter 1977-78. Interview by Kevin O'Neill.

O'Neill was at the time a 16-year-old office boy working on the children's comic Buster; his fanzine Just Imagine ran for six issues from 1975 to 1978. He later became a comic strip artist, first working with Pat Mills for 2000 A.D. (creating the character Nemesis), and later working with Alan Moore and Mills on notable comics including "Marshal Law" and "The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen". He also worked for Gerry Anderson on the film Five Star Five, which was abandoned just before filming started in 1979. The interview was conducted at Bray Studios in 1974, while the first series was still in production.

Editor O'Neill in cockpit of Eagle craft, one of the many elaborate sets built at Pinewood Studios for Space 1999.

A corner of special effects man Brian Johnson's office at Bray Studios. On the table top is a superbly detailed miniature that will be featured in one episode of Space 1999. The Voyager, with the original design for the Earthbound ship on the wall

JI: When did you begin your career as a special effects man?

Johnson: I began in special effects in 1958. I left school and worked in a laboratory, and I was responsible for more breakages of test equipment than anybody had ever remembered before (laughter).

I was offered a job by a man that I knew, Les Bowie, who's a special effects man in his own right. He was working with a company called Anglo Scottish Pictures, doing matte paintings for films at Shepperton Studios and places like that. He needed somebody to sweep the floor, so I gave him a hand sweeping the floor And then I became a camera assistant, by which time I'd joined the union - I worked on documentaries and feature films, and then left Anglo Scottish and worked for a commercial company up in town.

I went into the Air Force for two years, from the end of 1959 to 1961, and when I came out, Les offered me a job again. When I'd been in the Air Force, I'd been concerned with instrument landing systems, checking them out in various airfields all over England and Europe. I worked with Les on a picture called The Day the Earth Caught Fire that was really my first job as a special effects assistant.

After a number of other pictures for Les, I left and worked for Gerry Anderson on Thunderbirds, working with Derek Meddings.

JI: You mentioned working for Les Bowie on The Day the Earth Caught Fire, what other films did you work with him on?

Johnson: I did The Pirates of Blood River and The Phantom of the Opera, then we did Mosquito Squadron. And the others? Oh, I can't remember, there were so many for Hammer.

JI: Was this miniature work, or general special effects?

Johnson: Miniatures, floor effects, everything really.

JI: Was Les Bowie the man behind the Bowie Organisation, which dealt in special effects?

Johnson: Yes, which is now defunct.

JI: Was it just a group of freelance people?

Johnson: Yes, there was myself, Les, Pat Moore, who's dead now unfortunately. Nearly three quarters of all the British special effects men were in it at one time or another.

JI: This was completely independent of any studio?

Johnson: Yes, we had our own studios at Slough. We used to do the model shots there and go on various locations, we were spread all over the world at one time or another.

JI: And how did you come to leave that?

Johnson: At the time there wasn't much doing in the way of jobs and as a freelance, you take whatever comes first. So I went and worked for Gerry Anderson on Thunderbirds. Then I was asked whether I could work with Wally Gentleman on 2001.

JI: How was Space 1999 created?

Johnson: This series started with a basic idea - we all sat together and talked and built up ideas and worked out a basic format, then expanded on that. By the grace of good fortune we managed to get the companies who were interested in buying it to agree to pay a bigger unit price for each episode. Then it turned from l6mm (what would have been, I think, a l6mm diaster) into a 35mm spectacular.

JI: How have you approached this series, from the point of view of style?

Johnson: The thing I've tried to do with this series, is to shoot it almost like a documentary. You very often see special effects sets on the screen and because they've been set up by somebody who's fairly artistically minded, they're often more composed than a genuine shot would be. In other words, there's always a nice little tree over on the left hand side of the shot, balancing that on the right is a lump of rock. And in the background in the valley is a city, and the sky balances the whole thing.

I maintain that you don't necessarily have to do that. You should shoot something which people will not instantly take as a model. But there again you want to try and shoot it just the same as a cameraman recording an aircraft landing at London Airport who gets a wire fence in the way - make it realistic.

I think a lot of the things that will be seen in this series, considering how much they cost, would stagger some producers, when they look back at their costs on other series.

It's only a question of technique - for example, Polaroid film, light guides, lasers. All sorts of things come along. You adapt all these techniques to make things easier, and cheaper, and quicker to operate.

I think there are some shots in Space 1999, that stand up to 2001 quality - I think that's because I've got a good crew and we all work pretty well together. Of course there are other shots which are absolutely diabolical in Space 1999, which I deeply regret ever having started in the first place.

But when you're doing a Television Series, you have to balance the things you would like to do, with the amount of money you can spend. And I don't have an unlimited budget. In no way do I have an unlimited budget.

JI: Have you got a bigger budget than they had on UFO?

Johnson: No! For a start off we don't have a fraction of the people that worked on UFO. I've got twelve people working here, and that's it. On UFO they had considerably more than we have. And running through all the budgets and things, I think there's less money on this series, than there was on UFO for special effects.

JI: This must be the first Gerry Anderson series to incorporate people into the cockpits of the craft?

Johnson: That's right, yes similar to what we did on 2001. But we did it in a different way there. And, I suppose the basic idea is as per 2001, but the final effect is different, and the actual original approach is different too.

JI: More spectacular than just models though?

Johnson: Oh, I think so, yes. It ties the models and the people together. That's the thing which is all important. We do that as much as we can. And avoid having model people in shots.

In space you seem to get away with models. With totally black skies and stars models seem to be acceptable. Whereas with blue skies and model trees, they're not so good.

People don't have any idea what size our models are or any thing. On Star Trek the basic starship model The Enterprise was fourteen feet long. But when you see the footage they used in the series, they might as well made one three feet long! (laughter).

JI: How have you approached explosions in the series?

Johnson: We run at 120 frames per second, which gives us five times normal speed.

JI: And eats up a lot of film?

Johnson: Yes it does. Even that's not fast enough really. But the real problem is simulating explosions in space, where there is no gravity and no resistance. So you can't have flames, the explosion is faster, and it should radiate out in all directions rather than just go up, and then down again. Well we've overcome that. It's a bit complicated, but we've managed to produce bangs which go out in all directions, and which I think look fairly good.

JI: Have you ever worked with model ships? It must be a problem scaling the water?

Johnson: Yes, you can never win. Water turns into droplets, and the droplets are visible. Even the greatest, model special effects water shots, are killed stone dead because you can see droplets of water the wrong' size!

You've got to shoot them full scale. In other words they are visual life size models. If you want the Victory you've got to build the Victory 298 feet, or however long the thing was and shoot it full size. Otherwise, when it ploughs through the waves, there are bloody great droplets of water floating through the air. You see that and think well that was probably about 1/7th scale or something (laughter).

In fact with this one (Space 1999) that's one of the first things I said. Under no circumstances do we have any water, on any of the planet sets, or models. You just have to work out the fact that we have to shoot four or five shots on average a day, and then think of the difference between, is it worth spending X number of thousand pounds over the top and going behind schedule to scale the water or do we write another story, just as exciting, about a different situation which contains no water.

There are some things you just don't touch when you're doing a Television Series - that's all there is to it. Because it makes too much hard work, and it's not needed. You cannot go entirely into the realms of fantasy, when you're doing a Television Show which has to be on budget, and on schedule, and everything else, it's bad enough as it is.

Space: 1999 copyright ITV Studios Global Entertainment