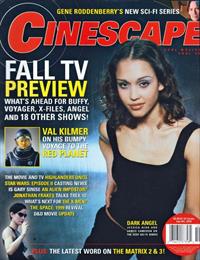

Cinescape

Cinescape was an American science fiction magazine which began in 1994, ending in 2004. This issue is September/October 2000, volume 6 number 6. This article, coinciding with the 2000 Space: 1999 convention, was written by John Muir, who has written novels for Powys and appeared in a documentary on the US Blu-ray release.

Twenty-five years after it began its all-too-brief TV run, Space: 1999 could be ready to blast out of limbo

When Space: 1999 landed on television in 1975, the ads didn't skimp on hyperbole. "The Future Is Fantastic!" they trumpeted. The syndicated series was touted as the next Star Trek - an ambitious, intelligent science fiction drama featuring top-notch special effects and an international cast. Yet while the series won critical kudos, impressive ratings and a devoted fan following, its future wasn't so fantastic: It lasted only two seasons.

But that fantastic future could still arrive for Space: 1999. After spending more than two decades in pop-culture oblivion, the series is blasting back into the spotlight. This fall, a 25th anniversary convention (sponsored by UnitedVision, Inc.) in New York will reunite much of the cast, and the series will land on DVD in early 2001.

"Space: 1999 is remembered because it was done with deep integrity, and the production values were brilliant," says 1999 cast member Zienia Merton. 'Whether some effects have become dated is unimportant; the integrity shines through." Catherine Schell (who played resident alien Maya) concurs that the series "remains beautiful in style and photography. Space: 1999 was ahead of its time...ageless...in so many ways."

The story of Space: 1999 begins with UFO, a single-season series about a secret task force monitoring extraterrestrial visits to Earth. "It was going to be another season of UFO," says Space: 1999 story consultant Christopher Penfold, "but it went through a number of metamorphoses."

When UFO's ratings deteriorated, the producers (Thunderbirds creator Gerry Anderson and his wife Sylvia) began working with Penfold, production designer Keith Wilson and special effects director Brian Johnson to launch a new series to takes its place. The last vestiges of the UFO connection evaporated when novelist George Bellak came on board to oversee the creation of the new show. Under Bellak's guidance, the show's premise took shape. The series would follow the adventures of 311 Moonbase colonists cast adrift in space after a massive explosion sends the moon hurtling out of its orbit around Earth.

Despite the far-out set-up, Bellak wanted the series to focus on human drama, not special effects. "My intention was to write a sci-fi series in which the lead characters were recognizable human beings with foibles," he recalls.

Bringing those human beings to life was an ensemble cast headed by Mission: Impossible stars Martin Landau (as Commander John Koenig) and Barbara Bain (as Dr. Helena Russell). Barry Morse (Lt. Gerard from the original Fugitive series) signed aboard as scientific genius Victor Bergman, while Prentis Hancock, having just finished the BBC series Spy Trap, portrayed Controller Paul Morrow. Australian actor Nick Tate was originally "cast in a small role as Alan Carter, to die at the end of the first episode." Instead, Carter thrived in a role Tate says was "very active. It was a boyhood dream come true." After months of auditions, the producers hired Merton (fresh from her success in the BBC's Casanova) to play Sandra Benes. "I had some extraordinary moments with Martin Landau, who is an extremely generous actor - and a very strong and physical one," Merton recalls. "In one episode, when Sandra was in a trance, Martin grabbed me by the neck so forcefully I thought I would end up in traction!"

Though Bellak envisioned the series as a drama with fully developed characters and strong storylines, Space: 1999 never skimped on sets and special effects. Hancock remembers being "immensely pleased at the size and scope" of a project he felt was destined to be a "sure-fire hit." Johnson had an ambitious vision for the series, as well. 'The opportunity to work on 1999 was a chance to do better than Star Trek," says the SFX pioneer (whose later credits include Alien and The Empire Strikes Back).

That ambition would come with a hefty price- tag: The series cost a then-staggering $275,000 per episode. Though that didn't scare off IV execs in Japan, who paid record-breaking fees for the series, the American networks balked. Unfazed, ITC Entertainment (the show's distributor) sold the series directly to local stations, blazing the first-run syndication trail that Star Trek: The Next Generation would follow years later.

In the fall of 1975, Space: 1999 began airing on 156 stations in the U.S., bringing it to 95 percent of American households. Viewers welcomed the series in record numbers and programmers enthusiastically dropped hits like The Six Million Dollar Man, Happy Days and Rhoda to air the new show in coveted prime time slots.

Space: 1999 wasn't the standard, action-oriented sci-fi fare TV viewers in America had to expect. It was a moody, cerebral series. "The series asked questions about the way we live now and where we're going in our lifetime," Penfold says. "And it was bold enough to tackle the big philosophical questions, confident it could take the audience on the trip."

"It had a very rare combination: style and substance," says Thomas Lowery, the president/CEO of UnitedVision, a non-profit company which raises funds for AIDS research and the National Parkinson Foundation. "There was no endless technobabble, no leading the viewers around by a leash." Episodes like "Death's Other Dominion" (a Shakespearean tragedy replete with cryptic prophecies), "Dragon's Domain" (a stylish precursor to the Alien film series) and "Force of Life" (an enigmatic story featuring a wayward life-form nourishing itself on the Moonbase's energy) established the fact that 1999 was an adult show that tackled controversial ideas and challenged its viewers to think.

Los Angeles Times critic Dick Adler was among those who noticed and appreciated Space: 1999's willingness to depict the dark side of the future. He compared the new series favourably to cult fave Star Trek, noting that Trek was born in the "optimistic, recklessly liberal 1960s," while 1999 represented a "realistic look at the limited options for survival facing mankind."

But despite the glowing reviews and Nielsen victories, trouble loomed for the series. Producers Gerry and Sylvia Anderson separated in 1975, and Fred Freiberger (the producer of Star Trek's much-maligned third season) beamed aboard as producer and story editor. Worried that the first season had been too ponderous and confusing, ITC gave Freiberger carte blanche to change the series as he saw fit. ' 'Year one possessed an air of melancholy film noir," says Lowery. "Year two provided us with a more action-oriented piece." The second season also witnessed the departures of Morse and Hancock and the arrival of Catherine Schell's Maya, a shape-shifting alien.

Seasonal differences are heavily debated. Johnson, for instance, labels the second season "utter rubbish." Despite her good feelings for Freiberger and the second season, Schell also says of certain episodes, "I couldn't believe I was having to speak some of the lines I was given." Merton also concurs with the general feelings Of discontent about the revamped format. "l loved working on year one," the actress says. "The bonus for me is that I have met some wonderful folk through Space: 1999. This has obliterated some less-than-pleasant things that happened to me during the second season."

In 1977, ITC cancelled the series in order to focus on feature films. At the end of the final episode, "The Dorcons," Moonbase Alpha was still wandering through the universe, forgotten forever by mankind. Or so it seemed....

So who rescued Commander Koenig and company from obscurity? As it turns out, it wasn't so much a who as a what.

"The Internet played a huge role in the resurgence of enthusiasm for 1999," says Robert Ruiz, creator of the popular Space: 1999 Cybrary fan site (www.cybrary1999.com). "Individuals from every nation, touched by Space: 1999, discovered that fandom wasn't dead at all. Thousands of others remember the series and hold it in high esteem."

Interest in the series has been stoked by Fanderson, Gerry Anderson's official fan club, which has released soundtracks and documentaries about the show. During the last two years, ERTL re-issued two 1999 model kits, publisher McFarland released a reference guide (Exploring Space: 1999), Columbia House issued 20 episodes on VHS, the series ranked sixth in "IV Guide's "Battle of the Sci-Fi Shows Fan-To-Fan Combat" poll and BBC2 re-aired the show in prime time in the U.K., much to the delight of Nick Tate. "I love that it brought in a new generation of fans," the actor says.

Yet there are still millions of genre fans who haven't discovered Space: 1999. Though the series ran in syndication during the 1980s and appeared on The SCI Fl Channel in the '90s, Space: 1999 isn't even a dim memory for many young viewers who were born after the show ended.

But there's still hope that a franchise could be born from the ashes of the long-dead series. Appropriately, in 1999 a production company called Kindred Media produced Message from Moonbase Alpha, a sequel to the series. The seven-minute film was written by the series original story editor, Johnny Byrne, and starred Merton as her popular 1999 character, Sandra Benes, who sends a message to Earth revealing the Alphans' fate. The film debuted at a Space: 1999 convention in Los Angeles last year, much to the delight of hardcore fans. "In look and feel it was as if Space: 1999 had never left us," enthuses Ruiz, who describes the film's premiere as a moment of "total surprise, awe and unbelievable elation."

Now that they've had a small taste of new 1999, fans want to see more. Adding to 1999's momentum: the release of the series on DVD from A&E/New Media Video in January and a possible series of novels from Powys Books. "We're taking as our model the line of Doctor Who novels published by BBC Books which have kept that series alive and spawned a TV movie and audio books," says Powys editor-in-chief Mateo Latosa (who's still in negotiations for print rights).

The 25th anniversary convention, taking place at Manhattan's Crowne Plaza hotel from September 1-3, has given fans more reason to hope for the future. UnitedVision has gathered 16 guests for the event, including many of the original cast and creative team (along with Battlestar Galactica's Richard Hatch and Star Trek's Grace Lee Whitney). "It would help if the fans show Hollywood that there is a strong base of viewers waiting for a new production by turning out in numbers," Lowery says.

So what does the series' star think of all this revival talk? Landau's interested - if the script is right. "If there were a 1999 movie, the script would have to be better than any show we ever did or else there's no sense in doing it," says the Academy Award-winning actor. "To do a mediocre film after all this time is not my idea of keeping the series intact." Landau, who feels that 1999 was "under-appreciated" in its time, does feel that any future production deserves full-blown treatment. "If you're playing with the big boys, your special effects have to be top-notch, and there has to be enough money in the budget, otherwise it looks cheesy."

The future of Space: 1999 depends on its reception in today's market. Hatch knows a thing or two about trying to relaunch a sci-fi series: He's created his own trailer for a proposed Galactica movie. "Both 1999 and Battlestar Galactica had the essence of what is lasting - universal themes and the right combination of elements," he says. "I've always felt the epic journey of Moonbase Alpha had a long way to travel," muses Byrne.

"Maybe one day we'll see it swing back into view." If that's the case, another prophecy could be realized, this one from Prentis Hancock: "We might end up doing the show in wheelchairs...."