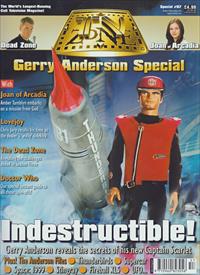

Gerry Anderson Special

Reviews from TV Zone, "the monthly magazine of cult television", an early 1990s UK genre magazine

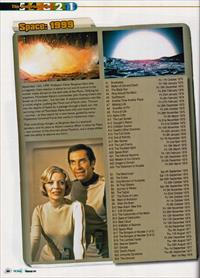

TV Zone Special 57 (Jun 2004), "Gerry Anderson Special". All the series are covered; 1999 is pages 54-57

Tony Cellini is a troubled man. Five years ago he led a spaceprobe to the planet Ultra, and was the only survivor. Now he's plagued by dreams of the mission, and Alpha's sensors pick up a graveyard of spaceships just like the one where he claims he met the monster... It's slightly perverse to name Dragon's Domain as the pick of Space: 1999's first season, as it's atypical of that season in many ways, and introduces many of the concepts that would become second season standards. There's Helena Russell's medical log (with a date, 866 days after leaving Earth orbit, set well into Season Two), apparently introduced here due to contractual obligations to ensure stars Martin Landau and Barbara Bain got a certain amount of screen time, even if the script was focused on a flashback to long-ago events. There's also a monster, in contrast to the conceptual enemies, from lonely computers to ghosts haunting those who've yet to cause their deaths, and philosophical themes that dominate elsewhere in Season One. But Dragon's Domain scores for one simple reason - it scares you rigid. The Dragon might be an immobile array of tentacles and a glowing light, but the blood is chilled by the eerie sounds it emits, Charles Crichton's dark direction, and the relentless way it sucks in its victims before spitting them out as mummified corpses mere moments later.

It all contrasts nicely with the 2001-esque depiction of the Ultra probe's long journey, and the scenes back on Earth which ensure this episode works as solid drama, bridging the gap between the Earthbound, highly political UFO and the more outlandish Space: 1999. In the mid- 1990s scenes, guest star Gianni Garko brings an intensity to his role that makes him credible as Koenig's one-time rival, and the pick of the Italian actors forced upon the series by its backers insistence on 'Euro-pudding' casting. Similarly, Martin Landau gives a subtly different performance as a younger, more enthusiastic Koenig (contrasting nicely with the rare moment of blazing anger he shows when Helena doubts his old friend and rival Cellini's sanity), who's yet to get the measure of cynical politicians like Douglas Wilmer's Commissioner Dixon.

The Moon approaches a planet that seems suitable for colonization. As Koenig considers activating Operation Exodus, sensors pick up a squadron of Hawks - laser-armed spacecraft from Earth. With no time to consider this apparent impossibility, Koenig has to take a split-second decision - whether to fire during the few moments available before they can attack.

A few days later, the consequences of his decision are clear. Alpha lies in ruins, and the crew's only refuge is a relentlessly hostile world.

War Games is the peak of Gerry Anderson's special effects achievement. From the opening moments, the tension racks up as regulars die, and Alpha is destroyed piece by piece, despite the heroism of its defenders. Things get all philosophical and weird later on, but the sense of desperation is maintained to the end.

So why mark it down as a disappointment? Well, for a start, there's the frankly bizarre performances of the usually excellent Anthony Valentine and Isla Blair as the aliens - a text book example of how not to 'act alien'. But more than this, there's the ending. It's all a dream.

Ok, so it's a dream with a point. The aliens wanted to discover whether Humanity had the maturity to live in peace with them, and on discovering that the answer's 'no', have let the entire scenario play out to show Koenig why there's no place for the Alphans on their world. But it still feels like a cheat that Anderson's using this idea so long after Tom Thumb Tempest.

After Koenig is affected by radiation from the Nuclear Waste zones and crashes his Eagle, he has to be held in sickbay as the Alphans get joyous news. An approaching spacecraft is a Swift, an experimental ship from Earth that's equipped with a faster-than-light drive. Now the Moon's been located, Earth can send a larger ship to evacuate the Alphans... and a lucky few can return on the Swift itself. But when Koenig emerges from sickbay, he claims the Alphans' saviours are disgusting protoplasmic blobs. Has he suffered undetected brain damage... or is he, as he insists, the only one who can see through the creatures' hypnotic disguise, and thwart their plans to ignite the remaining nuclear waste dumps?

There's little to praise in Space: 1999's second season, as ex-Star Trek producer Fred Freiberger displayed the understanding of Science Fiction that had been sooo successful on that show's final season, and dumbed the Alphan's battle for survival down to kiddiedom. Things only pick up in the final weeks, as left-over scripts from season one were exhumed from the 'round file' for budgetary reasons, bringing with them something of the thoughtfulness and philosophy of Alpha's first year.

Up 'til then it's monsters, monsters, monsters - unconvincing monsters, mostly. In The Bringers of Wonder, the aliens might be ambulatory tents (and vaguely reminiscent of the creature from Dragon's Domain), but with their disturbing single eye nested in a blob of protoplasm, they are at least weirder than the stuntmen in unconvincing lizard suits that dominate elsewhere, and more importantly, they're rarely seen, at least at first. The hallucinatory concept at the core of the episode is nicely paranoid, with Koenig's sanity in doubt (which provides an odd echo of the way Dragon's Domain debated Cellini's mental state), and the illusion the aliens offer cuts to the core of the series... it's not just a show about Humans exploring space, into which you can slot a script idea that would work equally well in Star Trek, Andromeda or Blake's 7. As with each of these shows, Space: 1999 is at its best when it plays to its unique selling point... it's about people forced to journey through the cosmos, longing for home...

Lonely teenager Shermeen Williams is seduced by her dream lover... except Vindrus is real. He's a creature from an anti- matter universe, who wants to transfer his people from his dying cosmos into ours. But to maintain balance, the Alphans must be sent the other way...

Anti-matter is the bane of television Science Fiction. From Star Trek to Doctor Who, it's been misunderstood by writers who latch onto the notion of 'opposite' and think 'parallel universe', 'evil counterparts', etc. Here Pip and Jane Baker give us a golden-painted man in lamé bathing trunks, who can only transfer his people from his universe into ours if someone makes the opposite journey. Not an equivalent amount of matter, which could almost make sense, or the individual's counterpart, but just anyone. As Science Fiction goes, Stephen Baxter it ain't.

Oh, and there's a monster called the Thaed. It's Death, backwards. Except not quite.

It's a pity, because there's a nice idea lurking in the other facet of the episode's concept. The teenager Shermeen's presence on the Moon strains credibility, particularly as the 'Days since leaving Earth orbit' quoted in Helena's log suggest she must have been about 12 at the Breakwaway, but the idea that someone who has no role and useful function might have been stranded on the Moon has potential. Indeed, its potential was played out very nicely, thank you, in the first season's Commissioner Simmonds, the politician who's left stranded on the Moon after breakaway, and meets an ironic end in the superb Earthbound.