Brian Johnson interview

An Interview with Special Effects Director Brian Johnson

By Steve Mitchell

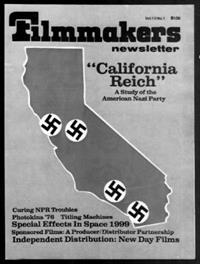

Filmmakers Newsletter Volume 10 issue 1 (NOVEMBER 1976) p23-28

Scanned by Paulo Jorge Morgado

"Space 1999", the highly successful TV space opera produced in England by sci-fi specialist Gerry Anderson, is the story of 311 men and women on Moonbase Alpha, an Earth colony in the year 1999, and their adventures in deep space after a series of thermonuclear explosions hurtled the moon out of Earth's orbit. Produced at a cost of $300,000 per episode, the show features Barbara Bain and Martin Landau, costumes by Rudy Gernreich, and superb production values -- most notable of which are the spectacular visual special effects.

As director/designer of the show's special effects, Brian Johnson is responsible for creating all the marvellous miniatures (spacecraft. structures, planet surfaces) as well as the intricate optical effects. Johnson and his crew work out of Bray Studios, the old home of Hammer Films, the renowned low-budget horror specialists. Oddly enough, Johnson began his special -effects career working as an effects man for Hammer years earlier.

Johnson started in the film business as a camera assistant and was promoted to camera operator when he worked with noted effects man Les Bowie on THE DAY THE EARTH CAUGHT FIRE.

From there he went on to Hammer and supplying such oddball things as edible, stain-free blood.

After Hammer, Johnson worked on Thunderbirds, a kiddie science fiction TV series (produced by his current boss Gerry Anderson) that used puppets instead of actors. In addition to imaginative puppetry, Thunderbirds featured elaborate miniature sets, vehicles, and air/spacecraft.

While Thunderbirds was Johnson"s introduction to the art of miniature special effects, the two and a half years he spent as a member of the distinguished effects crew on 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY developed and polished his skills. 2001 was an important influence on Johnson: it introduced him to the special problems of composition, high-contrast lighting, and the use of highly detailed miniatures to facilitate photography and increase credibility. Along with spectacular explosions and realistic zero-gravity effects, Johnson's mastery of these techniques has contributed significantly to the special visual appeal of "Space 1999" and its unprecedented popularity.

STEVE MITCHELL: How did you arrive at the design concepts for Moonbase Alpha, the Eagles, and some of the various other spacecraft?

BRIAN JOHNSON: I just imagined a colony on the moon and visualized a sort of modular construction for the things -- but being modular they could be expanded to whatever you wanted; you could take license with them.

For Moonbase Alpha I imagined the Control Center would be in the middle and everything else would radiate out from that. I originally envisaged the whole thing being underground, but then I was persuaded by Gerry Anderson that it wouldn't be visually very exciting if we didn't show something on the surface. So I added a lot more than I was originally going to and we made it much bigger than the original.

However this also allowed us to put new areas into the show without anybody realizing they weren't there in the first place. If you have a small complex, people begin to orientate themselves around that, so when you suddenly come up with a new section they say, "Oh, they added that? Where did they get it from?" But our thing is so big nobody knows where the hell they are anyway. It's like being in a city.

As for the Eagles -- well, I just imagined there would be satellite-bases all over the moon's surface because originally we were projecting it to be further on than 1999. So I figured you'd need a vehicle to lift off, carry people-inside, and set them down at the other end -- and the Eagle is what I came up with.

In fact, it was originally called the Modular Transportation Unit. The idea being that you could bolt Eagles together if you wanted to go further into space; you could piggyback the frames and the engine sections.

SM: There are a lot of impressive zero gravity effects in the show. For example, whenever an Eagle or a spacecraft takes off or lands the particles go flying across the screen. How do you do that?

BJ: Yes, they go everywhere -- just spin off. What I do there is always do my explosions with the camera on the ground looking straight up in the air and then when the explosion goes off it radiates out from a central point. If you did it normally, sort of horizontally, you'd get a flash and a puff of cloud that went up in the air and the stuff would come out and then start to drop again as gravity took over after the initial burst. But I do mine straight up in the air so the particles will go out and also sort of fall towards the camera -- it's strange and very effective.

SM: Do you shoot that sort of thing at any special speeds?

BJ: Yes. We do it about 120 frames per second. But recently I tried out a camera that is capable of shooting at 10,000 frames per second. It was developed by an English company, and it's used in weapons research and things like that. It's a prismatic device and it's reasonably steady.

We wanted to shoot something at 600. frames for a title sequence for one of the episodes. When you buy the camera you have to hire a technician to operate the mechanism. Well he inadvertently dialled 10,000 on the digital things. The camera was electronically keyed to kick off the explosions itself: it had a pulse on it, and when you wound the camera up to speed it pressed the button itself and set off the explosion. So we turned it over and it started going -- and to our horror it just kept going up to 10.000 frames, up to speed. And then bang! The explosion went off.

When we saw the shot the next day there was 5 seconds of nothing, black, while it ran up to speed and then you saw it go and it was unbelievable to see a chemical explosion -- gunpowder and flash powder -- going off at 10,000 frames a second. First you saw the initial charge flying off, then a flash followed behind it.

SM: Do you find this camera a help in creating certain zero gravity effects?

BJ: It's not steady enough to use except under exceptional circumstances. We're stuck with about 120 frames -- which is a pity, really. Sometimes it would be very handy to be able to go up to those sorts of speeds.

SM: What kind of cameras do you usually use?

BJ: We have one standard high-speed Mitchell 35mm, the definitive special effects camera, really. It's got such a marvellous movement. It's got registration pins, it's steady, you can rewind and run again, get multiple exposures on it. In the "Guardian of Piri" episode we did 16 exposures on one piece of film.

SM: Is that the show with the 14 Eagles flying down to the planet?

BJ: Yes. All 14 Eagles. So there were 14 passes on the Eagles, a pass on the planet is 15, and we had stars in there --so it was 16 exposures. It was wonderful!

SM: Were the stars a painted background?

BJ: No. I've got two techniques for doing stars: one using front projection and the other is artwork, which we burn in. The artwork is already made, so I can do it in about 5 minutes.

SM: What are some of the special problems you've encountered when photographing some or your models in action?

BJ: Getting rid of the wires, and trying to make them look bigger than they are - after all. our main Eagle is only 44 inches long. It would be nice to have a big one but we can't afford it.

SM: But you work with different size Eagles as well.

BJ: 44, 22, 11, and 5 ½ inches. It all depends on what space we have available at the time. Sometimes we need to be farther away but we can't be so we use a small model and compromise a bit.

SM: What kinds of materials do you use in constructing your various models?

BJ: We use brass tubing on the framework of the craft and hard woods of various sorts for the tank areas and we cover the models with little bits and pieces from plastic kits.

SM: You mean the model kits you buy in the store?

BJ: Yes. But it's the technique of putting it all together to make them look as if they do something when in actual fact they don't.

SM: What kinds of kits are they?

BJ: Mainly aircraft, kits and tank kits. We buy hundreds of pounds worth of kits from all over England. Sometimes we find kits are in very short supply -- Saturn V kits and Aurora Rebel kits, for example. Sometimes we scour the south of England to get enough kits to go around.

SM: Do you design the models' yourself?

BJ: Yes. Sometimes I'll model things in modelling clay or plasticine and get little bits of plastic card and stick them in and get an idea of the geometric shape and so forth. Then I commission the model -- do a very quick drawing to give the person some idea of what I want.

SM: Is the scale on those models the same size as your largest Eagle? Some of your alien spacecraft have appeared enormous.

BJ: Yes, but then we'll use a 5 ½" Eagle, so the prop isn't necessarily any larger than the 44" Eagle.

SM: What about problems like grain or snatching footage?

BJ: All the effects are done in camera. We don't do any optical effects except for ray guns and that sort of thing -- and very often we'll do those in-camera as well. For instance, if it's a static ray. So we don't really have a problem with grain or anything like that. We just have to make sure that if the main unit shoots an exterior, our shot that goes on either side of it is going to match it.

SM: What about problems in matching the lighting of miniature sets and a corresponding full-size one?

BJ: Frank Watts, the director of live-action photography, has complete control over the main unit shooting, and he's an exceptionally talented lighting cameraman. Plus he's really into things like mirror shots: using foreground mirrors, surface mirrors in front of the cameras, partially silvered mirrors to introduce light effects into the shot. So he makes my job much easier because if someone is suddenly caught in, say, a force field, he can often do it in the camera on the set.

And because he helps me that way, I help him by saying, "Don't worry about what you do -- we'll always match it. Just let us know what color gels you're using on the lamps for a particular sequence.'' Then he sends me that information and my lighting cameraman, Mickey Alden, and I discuss it and then just match whatever Frank"s done.

SM: Are you at all involved with the live -- action mechanical effects like the full-size moon buggies?

BJ: The moon buggy is a proprietary vehicle we bought and painted. I found the vehicle in the first place and thought it looked good, so we had one shipped over to the studio and Keith Wilson, the art director, used it right away. Then we built miniature versions, and now I have a radio-controlled version: it's 23 inches long and. it has fully proportional radio control gear in it.

SM: In "The Last Enemy" the moon is being used as a gun platform for two warring planets, and at the end one of the little buggies goes out to this enormous spacecraft gunship. What kind of scale was involved between the space ship and the buggy?

BJ: The buggy was about 5 inches long and the spacecraft was about 7 feet high. But you only saw a segment of it. In actual fact the model of the spacecraft was only about 6 feet long.

SM: In "Mission of the Darians" there's a spectacular shot of the interior of a spacecraft which is some 50 miles long by 14 miles wide; and they're walking through the interior of the spacecraft and there's live action going on a ramp. How was this combination of live action and matte work accomplished?

BJ: With foreground glass -- that is, a matte painting technique. You line up the actors on a strip of set on a floor and then take a sheet of glass and paint in all the background detail and make sure the actors' heads don't go through the painting. Then you light it and shoot the whole thing together. Foreground miniatures are very commonly used in war pictures and that type of thing.

If you start on a miniature and then pan across, you put the camera on a pivot point so you don't disclose the fact that the things which look as though they're a long way off are actually closer to the camera. And if you have something you want to get rid of and can't physically remove -- like a telephone pole or an oil derrick -- you have a matte artist paint something on this piece of foreground glass which will disguise what's behind. It saves you having to build a whole bloody set.

SM: You use a lot of explosives in your work. Have you ever had any trouble with them?

BJ: We have a problem in England because of this Irish trouble so we're very limited by the Home Office in what we can use and how we can use it. We have to hold Explosives Licenses even to store high explosives -- and that includes detonators, detonator cords, etc. Everything. That all has to be stored, and it's inspected by the Home Office every two weeks or so. You also have a list of everything you have in the place. It's a bit of a hassle, really. But we don't mind complying with it because it makes it much safer for everybody else as well.

We use a lot of fireworks and we also have to file a list of these. And then there are various classes of explosives and various divisions within those classes. For instance, fireworks are classed as Class 7, Division 2, which means they are stable and can be transported by air or sea at the discretion of the people transporting them.

SM: What about flash powder?

BJ: Flash powder's very tricky stuff because it's not terribly consistent. Some companies use more aluminium in their flash powder than others, and aluminium flash powder has unbelievable explosive qualities. So you have to be very, very careful and measure out very accurate doses of the stuff

SM: What kinds of specific problems have you had in blowing up things like spacecraft?

BJ: Nothing's really gone wrong; it's the sort of thing we do every day. And we don't use very large quantities so there are no real problems. When you compare the amount of stuff we use to what you would use in something like a war movie, it's a mere fraction.

SM: Have you ever blown up a set and then looked at the dailies and found the shot was unusable?

BJ: No. Some people do put in too much explosive, but I always measure my chemicals very carefully.

SM: You personally do the mixing and preparation of an explosive for a shot?

BJ: I have a number of assistants who usually do it. But when we're involved with actors, usually the person who's going to press the buttons will also mix the stuff and get it all ready. For instance, in Tamarind Seed I did everything myself because I was working directly with Julie Andrews and Omar Sharif. I simply couldn't afford to let someone else do everything and then walk up and press the button.

SM: In "Space Brain" there are some marvellous effects with antibodies flying through space and covering everything. How was that done?

BJ: I had aerosol containers made up with special chemicals in them. I can't tell you what the chemicals are, but the stuff just sort of floats out.

To film it, we turned the camera on its side and the Eagle was pointed up in the air and then all this stuff was let go by lads standing on the roof and just spraying the stuff down so it floated all over it.

SM: In "The Exiles" you have some 40 little canisters floating about. How did you do that one?

BJ: We had different size canisters and then we did multiple exposures. Then I artworked the really distant ones in just on black and we added those as a final pass. The result is the feeling of there being some here and some there. Of course I had to take artistic license because the canisters were only about 8 feet long and you're supposed to be seeing them as far as 300 or 400 miles away.

SM: In a couple of the earlier episodes we saw the maintenance area underneath the Eagle launching pads. Now I'm a special effects freak, but those shots were unfathomable to me.

BJ: It was all done in the camera. I used two Eagles and photographed them in various positions. Then I stuck on photographs -- just cut them out and propped them up. So when you see that thing with 10 Eagles in it, you are really seeing only 2 Eagles. The rest are just photographic cutouts lined up all the way back at the correct angles.

SM: Do you have any problems coordinating actors' reactions to effects you haven't done yet? I

BJ: No. That usually occurs on the kinds of shows which have big monsters coming in when in fact it's an assistant director waving a stick with a rag on the end: all the actors are watching that waving rag and then it's matted out and the actual monster's put in. But we don't use that sort of effect on this show.

SM: What about stop-motion animation?

BJ: We used it only once for a computer readout from an alien computer. But it was only for one shot. Stop-frame is too expensive and too time-consuming. When you've got to do 5 shots a day you can't spend 2 days doing one animated shot.

SM: One of the problems with television is the tight schedules. Do you have trouble maintaining a level of quality working under such pressure?

BJ: I have to average 5 special effects shots a day, 50 an episode -- that's an enormous amount, most people don't do anywhere near that. So I have to compromise on some things: there are often shots I don't like included in the show, but I have to let them go -- otherwise we'd spend days doing things and we can't afford that.

SM: What sorts of shots are you unhappy with?

BJ: Some aren't well-composed or a wire is showing but it's not too bad so we let it go because we can't afford to do it over. Sometimes the movements don't work the way we'd like them to because we used a multiple exposure technique and the timing wasn't as precise as it should be -- it tells the story, but not as well as it should. When these things happen I just grit my teeth, wince a little, and let them go -- and hope people won't notice too much. On the whole I'm pleased with what I see, but like any technician I'm always critical of my own work.

SM: I've read that the budget for the next season is higher. Does that mean the effects in season 2 will be more elaborate?

BJ: We've had 25% inflation in Britain in one year, so whatever increase we've had in the budget has been swallowed up in that. But even if we could spend a lot more money I don't think it would enhance the production value of the show. I don't mean it's the other components of the show which have to be cleaned up; it's just that you reach a point where the special effects can't really contribute greater production value even if you had twice as many.

SM: Do you ever start to think some or this is silly?

BJ: Yes. When you're working on a long running television series you begin to question your own judgement. You get rather punch-drunk with the whole thing because you're going from episode to episode and the shots start to repeat themselves but it's in a slightly different context so you can't use the exact same shots again. You see over and over "Eagle moves right to left. disappears toward Planet" -- but it's a different planet every time.

SM: I've noticed a different planet in almost every show. How do you do it?

BJ: I use a series of projectors which are motorized and slides with surfaces on them and then I project them onto various contoured surfaces. Then I usually add an atmosphere, just a slight haze, to a planet. I suppose it's a bit of a cheat, but visually it looks better.

SM: What about the surfaces such as the moon and the other planets?

BJ: The planet surfaces are invariably on stage with backdrops. But we need a new backdrop for the sky every week, so we build the model in the foreground and place the camera in a pit so we're actually on the studio floor. We don't use table-tops or anything like that. Our set-up is easier to work with because we can stand on it, and it won't shake or jiggle when we do the explosions. The backing is about 36 feet wide, so nothing is ever any wider than that: usually the planet-scapes are about 23 feet across in the background but obviously as you get nearer the camera they're wider by 5 or 6 feet.

SM: What kinds of materials are they made of?

BJ: Paint, vermiculite, polyurethane foam, masses of paint and powder, rent trees -- whatever we can get our hands oil that looks good.

SM: I suppose you really have to be resourceful when working for television. And that's something which doesn't happen overnight. What do you attribute yours to?

BJ: It just happens to suit my way of thinking. "Space 1999" was just the sort of show I'd always wanted to do from the point of view of producing a lot of effects in a short time without an excessively large budget. And knowing we had to get all those shots in time made me try to think of new ways of doing things like moon surfaces. For instance. I use a lot of photographic cutouts. All those shots you see of Moonbase Alpha are photographs.

One minute we have a clear stage and then we have to have a shot of Alpha and an Eagle just going over the top and it's just a simple matter of putting up the photographic cutout and then double-exposing an Eagle on top of it. But there are other people who, in order to get that shot, would have gotten a crew together and built the Moonbase section by section -- it would have taken a lot longer and been a lot more expensive.

SM: But your effect works

BJ: Exactly. It works.

Captioned Photos:

Space: 1999 copyright ITV Studios Global Entertainment