Alphan From Oz

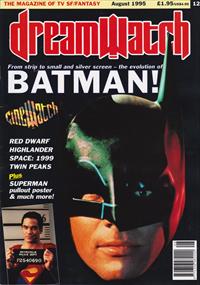

Dreamwatch was a UK sci-fi film magazine launched in 1994 (before it existed as a Doctor Who fanzine, DWB originally Doctor Who Bulletin). Competing against SFX and Sci-Fi Now, it eventually folded in 2007.

by Steve Eramo.

Dreamwatch (No 12, August 1995, p26-27)

Australian actor Nick Tate certainly landed on his feet when he joined the cast of Space: 1999. Hired to appear in the first episode, he was to play one of two astronauts who die after being exposed to nuclear radiation on the surface of the moon. Luckily, fate intervened and Tate found himself taking up a more permanent form of residence on Moonbase Alpha. The actor's rugged good looks, combined with his physical prowess and affable nature, made his character one of the most popular regulars on the series, particularly among female viewers, as he recounted recently to Steve Eramo.

The son of Australian husband and wife theatrical team John Tate and Neva Carr Glyn, Nick Tate was born in Sydney on 18 June 1942. When his parents divorced in 1951, Nick found himself travelling around the country with his mother, then touring with the John Alden Shakespearean Company. Nick's intense and prolonged exposure to the theatrical world would have an effect on the direction his life would take. "It was a great experience and I loved it," he recalls. "for me, I guess, there was no alternative. I was going to be an actor whether or not I really had the desire to be something else. At the beginning my parents didn't want me to go into the profession. In fact, before my father left home he did his best to persuade me to pursue another line of work."

Ultimately, the smell of greasepaint proved too tempting for the actor to resist. At fourteen he made his professional debut as Amal in the Sydney Opera Company production of Amal and the Night Visitors, and then appeared opposite his mother in two or three episodes of a new Australian television series, Long John Silver. "Television had arrived in Australia in 1957," reminisces Tate, "and I managed to get the role of a singing telegram boy in a production called The Skin of Our Teeth where I found myself falling in love with the whole process of how television is made. I was so intrigued by everything that I couldn't wait to get away from school and get a job in one of these places. There wasn't a tremendous amount of work around for young actors at the time, and since I also liked the technical side of the business, I decided to try my hand at becoming a director."

Tate left high school before graduating and managed to get a job as a studio hand for the Australian Broadcasting Commission (ABC). Over the next five years he worked his way up the ladder, doing everything from making tea to prompting actors during rehearsals. Such hard work and determination eventually paid off and he was made an assistant director. Not one to waste an opportunity, he took advantage of his flexible schedule at ABC and accepted a second job as a stage hand for the Independent Theatre in Sydney.

Despite his success at ABC and in the theatre, Tate was still apprehensive about making a full-time commitment to the precarious life of an actor. To bide his time he joined Australia's part-time Citizens Military Force. "For the first time in my life I really had to tow the line and meet a certain standard that I certainly never had to meet at home. I liked that."

Tate was then confronted with a task harder than any he had faced in the army, namely, what did he want to do with the rest of his life? It was his role as Tom Finlay, Jr. In a production of Sweet Bird of Youth that became the turning point for him. "Because of the success of this particular production, as well as my love and dedication to it, both my parents and I finally realised that I was probably going to be an actor for the rest of my life."

After appearing as a regular in two other Australian television series, the actor found himself at a crossroads in his professional life. In 1965 he chose to leave Australia and travel to England to explore opportunities there. Throughout the 1960s he worked extensively in repertory theatre, travelling around England and Ireland and eventually television work came along in such popular series as Dixon of Dock Green and Z-Cars. Tate went back to Australia in 1969 when he was offered an eighteen-month stint as Nicholas the Gallant in a hit musical stage production of Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, but returned to England in 1973 when he was offered a role aboard Space: 1999.

The exciting new SF show had received additional financial backing from Italy's RAI network, one of the contractual stipulations being that an Italian actor or actress had to be featured periodically. This was taken one step further and a regular Italian character called Alfonso Catani was written into the series. "I don't know what went wrong, but for one reason or another the Italian they had chosen to play the role of Catani didn't work out and at the very last minute they had to recast the part."

Thanks to director Katzin, Tate was given the chance to audition for the part of Catani, but in doing so he had to use an Italian accent, with "disastrous" results. After trying several European dialects, eventually the director tried to persuade the Andersons to let Tate read the part using his natural Australian accent. "Sylvia Anderson jumped in and said, 'No, Australians sound too much like Cockneys and we've already got a Cockney in the show.' At that point I saw red and, for the first time, really spoke up for myself. During the 1950s and 1960s the film industry had always used Cockneys to play Australians and in the end there were practically no Australians playing Australians. Being Australian I felt aggrieved about that and wanted to put it right."

The production team finally relented and let Tate read the role using his normal accent. Arriving home that evening, his agent phoned to offer him not the role of Alfonso Catani in Space: 1999, but that of Alan Carter. "I took the abrasive Italian arrogance they wanted in Catani and successfully transplanted it into an Australian astronaut named Alan Carter," says Tate with a smile. "I didn't have to dig too deeply with the character of Carter, he was pretty much all the things I was as a young man -- friendly, happy-go-lucky and someone who loved adventure and accepted a challenge."

"Generally speaking, it was a very happy time on the series. Martin (Landau) and I became very close friends while working on the show. I liked Barbara (Bain) as well, a very bright and friendly woman. Both of them are fabulous spellers with great vocabularies, and between scenes we used to play lots of word games together. I had great rapport with the rest of the cast as well, including Prentis Hancock (Paul Morrow), Clifton Jones (David Kano), and Zienia Merton (Sandra Benes)."

One of Tate's favourite first season episodes is "Another Time, Another Place," in which the Alphans meet duplicates of themselves living in a parallel universe. "That episode gave me a chance to get my teeth into a really good storyline," he recalls. Another early episode Tate remembers well, for quite a different reason, is "Dragon's Domain." Although the original script featured Alan Carter in most of the action, the version that ultimately reached production bore little resemblance to the script's first draft. "I know this episode was originally written for me because the writer (Christopher Penfold) invited me to his house and showed me the fist draft of the script," the actor explains. "The original story was very much like the film "Alien," where this creature kills everyone on board a space station, and Alan Carter is sent there to discover what has happened. What he ultimately finds is this creature waiting for him, but I didn't play the part. Because they had Italian money in the series, the Italians wanted one of their lead actors to play a large role in this particular episode. Up to this point the only large role we'd had were visiting alien villains; we didn't have any visiting nice guys, and in their wisdom the producers decided to rewrite the script ad replace me with an Italian actor (Gianni Garko).

While waiting to hear about a second season of Space: 1999, Tate appeared for Gerry Anderson in a one-off children's science fiction film which explored Einstein's Theory of Relativity, shown as an after school special on America's NBC network. "Gerry made an attempt to start another space series done entirely with British actors," the actor explains. "He cast myself and Brian Blessed in the leads, with the result being Into Infinity. It was a very enjoyable experience for me but I knew they weren't spending any money on it. The storyline was very thin and Gerry tried to patch it all together by using bits and pieces of the old Space: 1999 set. I venture to say the budget on this programme was about a quarter of what one episode of Space: 1999 would have cost, perhaps even less. I don't know whether or not he was just killing time while waiting to hear if Space: 1999 was going to be picked up. It really was put together very cheaply."

When the green light was finally given for Space: 1999's second season, Tate and his fellow cast members found things had changed drastically since working on the first season of programmes. Space: 1999 did have a future but Tate, along with most of the show's original cast, was not to be a part of it. "We were very happy with the series and expected to be picked up again within three months after filming those first episodes, but it didn't happen. After a gap of nearly a year we were all convinced that the show was finished and had been abandoned. One day word suddenly went out that ITC had decided to renew Space: 1999, but the only two people they wanted back were Martin and Barbara. The rest of the show was going to be totally recast, which just sounded insane. That first series had ten permanent cast members in it, along with about thirty extras who had worked on the show regularly. Instead of firing everyone, what they really should have done was make a change in direction by way of scripts.

"I don't believe they researched it thoroughly enough to find out why the show hadn't been as successful as they wanted it to be. One reason I think the cast was changed so dramatically was due partly to the fact that Gerry and Sylvia had divorced during that previous year. Sylvia had chosen the original cast for the most part and Gerry wanted to change everything she had done with the show. Unfortunately, this was not a good move. An American, Fred Freibeger, had taken over from Sylvia as the new producer of the series. Again, I don't believe he did his homework and didn't realise how popular I was with viewers. As a result, he hadn't invited me back to do the show's second series."

There could be no confusion over Tate's popularity during the airing of Space: 1999's first season. It was ITC that drew attention to the fact that the actor received over five thousand letters a week from fans around the world. He was also one of the first non-Star Trek actors whom fans invited to one of their conventions. News travels fast in the entertainment industry and, in this case, it traveled by warp speed between ITC offices in New York and the Space: 1999 production office in England. "When filming on the second series began, I talked to Prentis, Clifton, Zienia and all the others who had been in the first series. They all told me that they weren't being picked up either, so it was just a fact that I had to accept. Not long after this, Gerry Anderson invited me to come to Pinewood Studios where he told me, 'Right, we want you back on the show.'" Zienia Merton was the only other regular cast member besides Tate to be brought back to the series, together with extra Sarah Bullen.

"I said, 'I don't understand it -- I was told that none of the original cast apart from Martin and Barbara was needed and that you were changing all the actors and adding new regular characters.' Gerry then said, 'Well, eight scripts have already been written and that's the way it is, but we've recognised your popularity and feel the show wouldn't be the same without you. We'd like you to come back.' Naturally I felt flattered, but on the other hand I realised he had just told me that eight scripts -- ones that obviously didn't include Alan Carter -- had already been written. He then told me not to worry and that he would introduce me to the new producer Fred Freiberger.

"I must say that I missed Sylvia greatly because she was a wonderful woman and really understood the show. It was clear to me that when I met Fred he had no love of the original show at all. He invited me back to his house to meet his family, and while we were there told me that his kids were great fans of my character, Alan Carter, which was why he brought me back. I guess I've got them to thank for getting me back into the show!" laughs the actor.

In the episode "Space Warp," Tate's physical agility was put to the test when Catherine Schell's character, Maya, goes on a destructive rampage. Again, the hand of fate reached out when Tate was asked to perform a complex and dangerous stunt during the filming of this episode. "I did most of my own stunts on the series except for this one where my character had to be thrown over a medical table and onto the floor. This scene had to be shot from the floor upwards, which meant the ceiling had to be lowered and I would have to jump off a mini trampoline and land on the hard floor right in front of the camera, face first." I always had a stuntman alongside me, Tim Condrun -- a wonderful man -- advising me what to do, although he rarely appeared for me since I did most of my own stunts. When it came to this scene I said to him, 'I don't think we should do this stunt because the ceiling is too low and I can't get a proper roll when I go over the table.'

"Tim agreed that I shouldn't do the stunt and stepped in to do it for me. When he landed on the floor in front of the camera he snapped his two front teeth out and dislocated his shoulder. I thanked him and helped him out a little bit but you could never replace a man's two front teeth. I want to take this opportunity, be it twenty years later, to publicly acknowledge Tim and express my gratitude to him for taking that fall for me!"

Despite the cast changes, script rewrites, and new sets and music, the second season of Space: 1999 did not quite manage to deliver what ITC promised to be a show "bigger, better, more exciting than ever!" The lights on Moonbase Alpha went dark forever after the cast and crew filmed the series' forty-eighth and final episode, "The Dorcons." "The show's original concept had been conceived by both Gerry and Sylvia Anderson. When they broke up it really destroyed much of what had been established during its first series," states Tate. "It seemed as if Gerry was prepared to allow somebody else to come in and totally change the humanity Sylvia had brought to the programme. We moved further away from science fact and started moving deeper into stories that had a much weirder slant. In the second season we wound up having, I think, some very silly characters. We weren't able to spend either the money or time on the original concepts, and as a result many of the creatures we encountered looked more like pantomime dragons.

"One of the reasons why I feel Space: 1999 eventually folded was because the second series didn't have the same sense of truth and honesty about it as the first did. That's not to say that I didn't like doing the second series -- some of the episodes we did were very good -- but overall I think our best shows were those first twenty-four.

After co-staring in the American CBS TV series Dolphin Cove, which was filmed in Australia, Tate flew to the United States to audition for a part in Fox's new comedy series, Open House. He won the role and, following the series' success, moved his family to California. He worked steadily in a number of American TV shows and in 1990 slid back into the pilot's seat as a guest star in the Star Trek: The Next Generation episode, "Final Mission." "I felt very much at home back at the helm. Dirgo was a wonderful character and, strangely enough, a space pilot," laughs Tate. "Of course , where Alan Carter was a sweet guy, a man of action, and incredibly loyal, Dirgo was gnarly, grisly, grumpy, and anything but loyal. He was like Carter in one way, however, in that he was good at his job.

"Patrick Stewart (Captain Picard) was a gentleman and easy to get on with. We had never met before but both he and I worked a lot in English theatre and as such had much in common. He told me of his great love for the stage and that he missed doing Shakespeare and all the classics. I commiserated with him but said I bet there are a thousand Shakespearean actors out there who would give their right arms to be doing what you're doing. Don't give it up, mate.'"

Lately, Nick Tate has been spending more time in front of a microphone than a camera. He has become one of Hollywood's leading talents for providing the narration behind advertising campaigns and movie trailers for such major motion pictures as Jurassic Park, The Shadow, Clear and Present Danger, Stargate, Drop Zone, and Outbreak.

As the year 1999 moves closer to reality, to what does Tate attribute his fans' loyalty to him and Space: 1999 over the last twenty years? "High production values, thoughtful storylines, strong acting, good directing, and, in the end, staunch and loyal fans," he unhesitatingly answers.

by Rob Pritchard Pages 28-30

Space: 1999 is twenty this year. To mark its coming of age, Rob Pritchard charts its trajectory, from its confused origins to its ultimate demise.

Space: 1999 began life as a sequel to Gerry and Sylvia Anderson's first live action series UFO, which told of Commander Ed Straker's battle against invaders from another planet. Hidden beneath a film studio, Straker's organisation, SHADO, fought the invaders on Earth, in space, and on the Moon. Following UFO's premiere in America, the CBS network expressed interest in a second series, and, since those episodes set in space had proved most popular, the Andersons and their team set about revamping the series along space-bound lines. The new UFO would therefore be set on the Moon and feature a much larger moonbase. Indeed, the exterior of Moonbase Alpha, as it is seen in Space: 1999, was originally designed as the new "UFO" Moonbase.

When "UFO"'s ratings began to decline, CBS subsequently withdrew their interest, but the idea of a series set entirely in space was lodged in the mind of Abe Mandell, ITC's New York head. In discussions with Mandell and Lew Grade, ITC's managing director, the Andersons came up with the idea of Earth's Moon being blasted out of its orbit, carrying with it a manned Moonbase.

Such an expensive production -- the first series reputedly cost three million pounds -- was squarely aimed at America, the biggest and most lucrative television market in the world. Since ITC New York had been distributing Grade action-adventure series for almost twenty years they could be expected to know something of American tastes and the Andersons found themselves having to accept their advice.

An example of this was their insistence that the Andersons cast in the leads ex-Mission Impossible stars Martin Landau and Barbara Bain in order to secure a network sale. The Andersons duly obliged, although Sylvia later remarked that she never wanted a husband and wife team as the leads. Landau played John Koenig, the stern Commander of Moonbase Alpha, with Bain as Dr. Helena Russell, head of the Moonbase Medical Centre.

The show's other major role, that of Professor Victor Bergman, was taken by Barry Morse. Morse was another familiar face to American audiences because of his role as Lt. Gerard in the 60s adventure series The Fugitive (1963-6). Supporting roles were taken by a largely British cast. Prentis Hancock played Paul Morrow, Clifton Jones was David Kano, Zienia Merton played Sandra, Anton Phillips was Bob Mathias and the young Australian actor, Nick Tate, played Eagle pilot Alan Carter. With the exception of Tate, however, most of the cast would be notably underused.

The Andersons brought in an entirely new set of writers and directors for Space: 1999, perhaps mindful of the fact that its predecessor, UFO, had featured weak scripts and a number of poorly directed episodes. But Space: 1999's eleven writers -- chief amongst them story consultant Christopher Penfold and story editor Johnny Byrne -- worked under very difficult conditions. Shooting on the show began at Pinewood Studios in November 1973, but as the episodes were completed the Andersons must have felt that they were making Space: 1999 not for a mass audience but for a handful of American executives. As Johnny Byrne recalled, "There were endless doubts and worries in the minds of people we never met -- mainly in New York."

Scripts were constantly rewritten to satisfy their demands, which would often change from week to week. This in turn caused serious production problems which are evident in a handful of poorly written and badly structured episodes. However, as the series progressed, the writers found their "space legs" and turned out many good episodes, including "Earthbound" and "Death's Other Dominion." Perhaps the biggest problem in Season One occurred when the money ran out and production of the show was suspended.

As Gerry Anderson recalled, "When we ran seriously over budget, we had to go back to Sir Lew. He saw what we had achieved already and instantly gave us the extra money." It would be interesting to know whether this "extra money" arrived from RAI, the Italian state television company. Whatever, RAI's arrival as co-producers mid-season put further pressure on the writers, since four episodes would now have to feature an Italian guest star.

Space: 1999 benefited immensely from its talented team of five directors headed by Charles Crichton. More recently Crichton is best known for directing A Fish Called Wanda, but his reputation is built on his work for Ealing films, including directing one of the five segments which comprised the horror film Dead of Night (1945) and the comedies Hue and Cry (1946) and The Lavender Hill Mob (1957). American Film director Lee H. Katzin was brought in to helm two episodes, including the series opener "Breakaway" which set the standard for the show.

Particularly impressive was the work of ex-Avengers stuntman turned director, Ray Austin. Of his seven episodes, "The Troubled Spirit" boasts a brilliantly sustained opening and the episode as a whole is a television rarity -- a genuinely scary ghost story. Even better is "Mission of the Darians," a ghoulish tale brimming with imaginative moments both touching and grotesque. David Tomblin was the show's most consciously stylish director and could take a weak script, such as "Force of Life," and make it acceptable through sheer style. But give him a good script to work with such as "Another Time, Another Place," and the result was a classic telefantasy episode.

Although the writers and directors were largely new to Anderson productions, the key production personnel were all long-time associates. These included production designer Keith Wilson, special effects director Brian Johnson and composer Barry Gray.

Much of the show's budget was spent on its sets and a succession of internationally known guest stars including Christopher Lee, Joan Collins, Margaret Leighton, Leo McKern, and Peter Cushing. Even twenty years on, the sets which Keith Wilson and his team created are some of the most stunning ever seen in TV SF, a good example being Alpha's nerve centre, Main Mission. This was a set so vast that it afforded Space: 1999's director's an almost infinite variety of camera angles. Complementing the huge sets was a dazzling use of colour, usually seen when the Alphans encountered some alien planet.

Special effects director Brian Johnson had worked on 2001: A Space Odyssey as part of the large effects crew, and the influence of that film is evident on the model work and the full size Alpha sets. With less money and a smaller crew (twelve people) than the special effects team on UFO, Johnson used an entirely different set of techniques to create the show's VFX. Wherever possible the model spacecraft remained stationary as the camera tracked past them thus creating the illusion of movement. Superimposition -- rewinding the film while still in the camera -- enabled planets and stars to be added as required. This technique also created fleets of ships where only one model existed and gave the shots a tremendous sense of perspective.

Another innovation came with the show's explosions, which were filmed with the camera pointing directly upwards, resulting in a spectacular effect. One notable difference from previous Anderson shows was the absence of any stories set at sea. This seems to have been at Brian Johnson's insistence (since water is, of course, impossible to miniaturise), and caused the loss of one story in which Paul Morrow and David Kano found themselves adrift on an alien ocean. Plans for the episode involved location filming on the south coast before it was finally abandoned.

Mention should also be made of Martin Bower, a talented young model maker who sent Gerry Anderson photographs of his work and subsequently found himself employed to build the spaceship models, many of which were re-used from "Alpha Child" onwards.

By March 1975, the first series was completed and sold to over one hundred countries in the summer of that year. These twenty-four episodes told the story of Moonbase Alpha's 311 inhabitants following a nuclear explosion which pushed the Moon out of Earth's orbit and into deep space. Having no control over their journey, the Alphans encounter planets, space storms, and aliens by the score. Underlining all this is the desire of the Alphans to find a habitable planet where they can settle.

If Season One of Space: 1999 owed a debt to anything it was not, as its critics desperately insisted, to Star Trek, but to 2001 with its sense of wonder and predestination. These qualities are evidence in all the Season One episodes and go some way towards compensating for the often underdeveloped characters. The feeling of awe and wonder is underlined by Barry Gray's impressive orchestral score and the use of carefully selected pieces of classical music.

Particularly pleasing is "The Testament of Arkadia," in which the Alphans are forced into investigating an apparently lifeless planet only to discover humanity's origins. Such metaphysical attitudes irritated many critics brought up on Star Trek, a show whose message ascribed across the cosmos was, "Hey -- we can do it!"

Space: 1999 may not seem as optimistic, but this has less to do with poor writing than with its distinctly British/European view of science fiction, which tends to be tougher, harsher and more pessimistic than the American equivalent. If, after twenty-four episodes Koenig and crew remained underdeveloped characters, then something else came through to fill the gap -- a remarkable sense of wonder which does justice both to the immensity of space and the almost hopeless struggle of the Alphans.

Despite Space: 1999's popularity, as evidenced by sackfulls of American fan mail, ITC were very much hedging their bets on the prospect of a second series. Perhaps because they would now be wholly funding the show (following RAI's departure), ITC New York asked Gerry Anderson to find an American story editor to work on the series. Another significant event that followed the filming of Season One was the separation of Gerry and Sylvia Anderson.

Anderson found Freddie Freiberger, a man who'd worked in American television as a writer, story editor, and producer, and who would work in all of these capacities on Space: 1999. After viewing eight episodes Freiberger insisted on more characterisation and humour. These were genuine weaknesses in the show which the cast and crew were aware of and wanted to improve upon. Unfortunately, beyond the show's production values Freiberger didn't care for Season One in the least and set about a wholesale revamp of the show's format.

Freiberger asked for fast-paced, straightforward SF stories with the emphasis on characterisation; and early episodes -- such as "The Metamorph" and "Journey to Where" -- fulfil this brief admirably. Character-wise, Koenig's love for Helena is made obvious and is demonstrated in the shape of jealousy in an early Season Two episode, "One Moment of Humanity."

Barbara Bain's acting also improved, although her character could still be a little too twee at times. In a general sense, too, the Alphans are much more relaxed with each other. In line with this, the costumes were redesigned by Keith Wilson and Emma Porteous to create a more informal appearance.

For the second season the Alpha sets were cannibalised to form a much smaller Moonbase. Main Mission was replaced by a set barely half the size and renamed Command Center, the official reason being that this emphasised the characters and their predicament, but in doing so the show lost far more than it gained. Alpha was reconstructed as a standing set (minus part of the Access Corridor linking the Eagle cockpit to the passenger module!) which was all the viewer ever saw, so over-familiarity quickly set in and consequently Alpha seemed a much less exciting place than in Season One.

Obviously taking no prisoners as far as Season one was concerned, the producers recast virtually all the secondary characters, Zienia Merton reappears sporadically as Sandra, but as for Professor Victor Bergman, he died because of a faulty spacesuit -- well, supposedly. A scene explaining his demise was written for Season Two's opener, "The Metamorph," and may even have been filmed, but it never made the final cut. In his place stepped Maya, introduced in "The Metamorph" and joining the Alphans following the destruction of her planet, Psychon. Maya was Freddie Freiberger's creation and, amazingly, seems to have been the one thing that persuaded ITC to go ahead with a second series, confirmed to the press on 15 December, 1975. Production began six weeks later.

Much of the humour was given to Maya and revolved around her shape-changing ability. Superbly played by the Hungarian born Catherine Schell, Maya's character is intrinsic in that it indicates the general area into which the show was moving -- from science-fiction to fantasy. Maya's abilities unleashed an avalanche of monsters onto the show, but the effectiveness of her transformations was usually hampered by a clumsy theatrical insistence that she turn and look directly into the camera as she transformed.

A number of stories prominently feature monsters, including the three scripts Freiberger wrote under the pseudonym Charles Woodgrove. These were "The Rules of Luton," "Space Warp," and "The Beta Cloud." The best was Terrence Feely's two-part "The Bringers of Wonder." Like the spaceship models, the monsters were designed by Keith Wilson for constant re-use by attaching different appendages and spraying them different colours. The demands were such that, invariably, the occasional monster was less than effective, but in general the standard was quite high. There was an obvious temptation for the writers to use Maya's superpowers as a way of saving the Alphans, but although this does happen in "The Seance Spectre," "A Matter of Balance," and "Brian the Brain," most episodes commendably avoided this.

Billed fourth after Maya was not, as regular viewers might have assumed, Nick Tate, but yet another new character, the Italian security chief Tony Verdeschi played by Tony Anholt. Verdeschi's character was given an affectionate/humorous relationship with Maya, presumably intended to balance the "mature" love affair between Koenig and Russell. By popular demand Nick Tate returned as Alan Carter, but the actor found himself very much on the sidelines in this new format. Unsurprisingly, Tate's relationship with Freiberger was not a happy one.

Season Two had sixteen writers over twenty-four episodes suggesting that the writers found it difficult to adjust to this new format, and the fact that Freiberger wrote three of them himself -- under the alias of Charles Woodgrove -- would seem to confirm this.

Many of the year one directors were replaced for Season Two. Charles Crichton and Ray Austin stayed on although Austin subsequently departed after two episodes to work on the first season of "The New Avengers." The six new directors included Val Guest (The Day the Earth Caught Fire 1961); Peter Medak (The Krays 1990) and Tom Clegg who, prior to Space: 1999, had worked on The Sweeney.

Supervised once again by Brian Johnson the special effects were even glossier, although with less of an emphasis on huge spaceships and explosions. Instead new pieces of hardware are often substituted, including Alpha's laser cannon ("The Metamorph") and the beautifully detailed laser gun for the Eagles ("The A B Chrysalis"). Particularly stunning was an ingenious and cheaply done version of the famous "slit-scan" effect developed for 2001 and first seen in the Gerry Anderson produced special Into Infinity (AKA The Day After Tomorrow), which had had an exciting, rock-like score by Derek Wadsworth who was brought in to provide more of the same for the faster pace envisaged for Season Two.

If Season One started with a number of poor scripts before improving, then Season Two is the reverse of this. By mid-season episodes such as "Space Warp" and "The Seance Spectre" display no interest in story or character and work only as a series of spectacular set pieces smothered in Derek Wadsworth's music. The latter also illustrates how the show's internal continuity was blatantly ignored for the sake of "action." The baddie Sanderson and his motley team are allowed to wander unhindered throughout Alpha causing immense damage, yet nobody thinks to cancel their comlocks as Kano did when Tony Cellini went on the rampage in Season One's "Dragon's Domain." Increasingly the show seemed to be pitched not at a mass audience but towards its more undemanding fans.

Unlike year one there is a noticeable lack of big name guest stars and an irritating habit of dubbing British character actors with American accents (i.e., John Alkin in "The Mark of Archanon"). That said, episodes such as "The A B Chrysalis," "The Bringers of Wonder," "The Lambda Factor" and "The Immunity Syndrome" all have their moments.

Also reasonably successful were two episodes pitched at a humorous level: "Brian the Brain" and "The Taybor." Undoing much of this, however, was Freiberger's insistence that the show end on a relaxed "family feeling" resulting in banal exchanges of dialogue closing most of Season One where the writers at least attempted to end their episodes on a thoughtful note.

Late into the second season, the production schedule of one episode a fortnight was increased to two to keep up with imminent American air dates. Eight episodes were made in this hurried fashion, resulting in the regular cast being segregated and a number of new characters brought in to fill the gaps, including John Hug as Eagle pilot Bill Fraser -- who had first appeared in "The Metamorph" -- Sam Dastor as medic Ed Vincent and Alibe Parsons as a communications officer. Due to the nature of their casting these characters were woefully developed and production mistakes are increasingly evident, reaching their nadir in "A Matter of Balance" where a crewmember idly strolled by in the background on the apparently lifeless planet of Sunim. The final episode of Space: 1999, "The Dorcons" -- produced over Christmas 1976 -- with its spectacular battle sequence seemed like an attempt to recapture former glories, but by this time in the USA the series had gradually slipped in the ratings and ITC cancelled the show early in 1977.

Perhaps the obvious reason for Space: 1999's failure were the childish scripts on offer for most of Season Two. The initial intentions may have been good, but the following through was lacking. As the season progresses, stories, characters and humour are all sacrificed for the sake of crude "action"; crucial aspects of the original format, such as the Alphans' desire to settle on a habitable planet, are thrown away; the alien planet-scapes, while lavish, are often disappointingly traditional (i.e., green leaves and blue skies).. There is little, if anything, to compare favourably to Season One.

All of which leaves one crucial question. Why did Gerry Anderson accept all these changes? Did he really have so little faith in his own show? Nick Tate's opinions this issue may shed some light on this -- did Anderson go along with Freiberger in order to eradicate the involvement of his ex-wife, Sylvia, from whom he had recently and unhappily separated?

One final irony. In the summer of 1977, a film from 20th Century Fox brought SF/fantasy into the mainstream as never before, with many SF TV series evolving as a result of its success. Had Space: 1999's producers taken a little more care, the show could have ridden the enthusiasm generated by Star Wars and gone to a third, maybe even a fourth series. A great shame, and a terrible waste.

Thanks to Ggreg Perry and Robert Ruiz, Allen Barnella