Trek vs 1999

Cue, Vol. 44, No. 47, dated December 20, 1975, for December 20-December 26, pages 61-63

Cue was a weekly event listings magazine in New York (similar to London's Time Out), running from 1932 to 1980. Michael Jahn was a rock music journalist who became an Edgar Award winning mystery writer. This issue also included an article by Isaac Asimov.

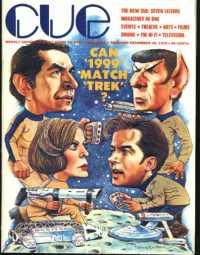

The cover art was by Calvin (Sandy) Huffaker (1943-2020), a political cartoonist who was twice nominated for a Pulitzer Prize for illustration.

Space: 1999 was shown in New York on WPIX-TV Channel 11, and on Sunday 21st December 1975 6:30 pm it was showing a repeat of Dragon's Domain.

The conflicts are all mysterious but the philosophies in Space: 1999 and Star Trek are different

By MIKE JAHN

Really, this whole thing has gotten entirely out of hand.

Who would have thought that a ten year-old television program about a bunch of people flying around in a space ship would turn into one of the major phenomena of popular culture? Yet Star Trek, which ran on the NBC-TV network from 1966-1969, has become a phenomenon indeed, not only in television, but in publishing and manufacturing as well.

Judy Lynn del Ray, an editor at Ballantine Books, which publishes a Star Trek series, says that "looking at what sells in the book market today, one would have to assume that sex, "Star Trek," and cooking are the three biggest things in America."

Star Trek is, in ways to be documented shortly, on the top of the science fiction mountain. But as always, one man's favourite is another man's target, and Star Trek is being challenged-by a British import called Space: 1999. Like its decade-old competitor, Space: 1999 is lavish, fanciful, and popular. It too is winning for the independent stations on which it runs more than double the ratings to which they have become accustomed. It too is introducing a line of books and toys, and, like Star Trek, gets lots of publicity. Will Space: 1999's Martin Landau shoot down Star Trek's U.S.S. Enterprise, as suggested by the artist who painted the cover of this week's Cue?

Before we tackle that question, a brief rundown of both series. Star Trek was created and produced by Gene Roddenberry, a Hollywood scriptwriter who, according to the best-selling book "The Making of "Star Trek,"" spent six years on the project and put more thought into it than went into the Bible.

As it finally appeared on the air, Star Trek told the story of the U.S.S. Enterprise, a large space cruiser operating in the 22nd century. Commanded by Capt. James T. Kirk (William Shatner) and his First Officer, Mr. Spock (Leonard Nimoy), the Enterprise was commissioned to explore the known portions of our galaxy, to make friends, defeat enemies, and, in the words of the show's title sequence, "to boldly go where no man has gone before." The Enterprise's mission was to last five years, but Star Trek itself was cancelled by NBC after three years and 79 episodes.

But Star Trek didn't die upon its cancellation in the spring of 1969. It went into syndication-that glorious graveyard where old network programs go to make the real gold. Star Trek continued, rerunning each episode over and over again, on more than 100 TV stations across the country. In syndication, it promptly garnered more popularity than it ever had while on the NBC network. A cult developed around it, and the cult itself quickly grew into a movement. Star Trek fans, called "Trekkies," began to hold conventions and exchange mimeographed newsletters, called "fanzines." Books appeared. Ballantine brought out "The Making of Star Trek" and two other volumes on the show. Bantam published a series of novelized versions of Star Trek episodes, and Ballantine shot back with novelized versions of an animated cartoon Star Trek that had blossomed on NBC's Saturday morning children's schedule. Toy manufacturers brought out dolls (called "action figures" in the trade) of Capt. Kirk and other members of his crew, plus models of the Enterprise, several enemy vessels, and a host of other things, including a twenty-dollar pair of walkie-talkies that look like the Star Trek communicators."

It was apparent that Star Trek had become more than just a fad. It had become a creature with a ravenous appetite for new information. One suspects that so many people began to imagine that the Enterprise, its crew and its milieu were real, the need grew to make it real. Thus Ballantine came up with "The Star Trek Blueprints," detailing every square foot of the Enterprise. That has sold 320,000 copies at five dollars each. Ballantine is now publishing "The Star Fleet Technical Manual," sort of a 23rd-century version of "The Marine Corps Manual," which contains all you need to know not only about the Enterprise, but about the entire mise-en-scene of the United Federation of Planets, under the aegis of which the ship operated. There is an Articles of Federation based upon the U.N. Charter, insignia of various Star Fleet Armed Forces grades, descriptions and details of the various types of fleet ships, and on and on, oft with authentic-looking technical drawings. The "Manual" sells for seven dollars and has a first printing of ... that's right, 450,000 copies. Watch out, Harold Robbins.

There are other Star Trek purchasables, and even two specialty shops to purchase them in. One of them is the Federation Trading Post, located at 210 E. 53rd Street in New York, which sells nothing but Star Trek material.

In the midst of all this success arrives the interloper. Space: 1999 comes from England, produced by the same outfit which provided American television with The Protectors, My Partner, the Ghost, Department S, and, significantly, a commercially unsuccessful sci-fi series which ran in the 1973-74 season, UFO

A spokesman for the Independent Television Corporation, which distributes Space: 1999 to about 150 American television stations, denies any connection between UFO and Space: 1999, but there are too many similarities to be ignored. UFO, set in the year 1980, has a Moonbase built to defend Earth against marauding aliens, it has sleek, futuristic uniforms and sleek, tight-tipped personnel who shoot first and ask questions later. UFO also has very good special effects, and may be seen Saturdays from 5-6 p.m. on Channel 9.

Space: 1999 has a Moonbase built to defend Earth against marauding aliens, and features personnel wearing sleek, futuristic uniforms who also shoot first and ask questions later. It's set in the year 1999, and the Moonbase has been expanded to include forces for scientific exploration. Man has also been using the far side of the moon as a dump for nuclear waste. In the pilot episode, this nuclear waste blows up, acting as a rocket which pushes the moon out of the Earth's orbit and into an endless series of encounters with other planets.

Like the Enterprise, Moonbase Alpha is going where no man has gone before and meeting much the same type of alien, but unlike the Enterprise, it is doing so unwillingly. And unlike the crew of the Enterprise, the citizens of Moonbase Alpha greet each new encounter with suspicion bordering on hostility. Their feelings are understandable. The cruise wasn't their idea. But the hostility doesn't make them likeable, and for a TV show to be successful, one simply has to like the characters. UFO had effects that were as good, and believable scientifically, whereas Space: 1999 is hopelessly out-of-line with anything resembling fact, as sci-fi writer Isaac Asimov points out on page 63. [In fact the Alphans were rarely hostile, apart from reluctantly in War Games]

But Space: 1999 is popular.

One way of rating TV shows is called "share of audience," that is the percent of those sets in use which are tuned to the show in question. The average share of a New York independent station in the early evening hours is 6 or 7.

Space: 1999, seen Sundays on Channel 11 from 6:30-7:30 p.m., earns a share of 19 or 20. Star Trek, seen on the same station from 6-7 p.m., earns a share of 13 during the week and 21 on Saturdays. So Space: 1999 isn't doing badly.

It also has managed to alienate most of the Star Trek partisans. The ones to whom I have spoken recently claim not to watch Space: 1999 and wince even at the mention of it. One person with an opinion on the subject is the writer D.C. Fontana, who served as story editor of Star Trek for half of its three year run and wrote eight episodes.

According to her, "1999 suffers from the same problem its makers had with UFO The technical effects are excellent, but they don't create people you care about. They got caught up in what Gene Roddenberry is fond of calling The Wonder Of It All Syndrome." That is, all special effects and no story.

Fontana is proud of Star Trek's adherence to fact. "The first people we consulted were at NASA," she says. ."Then somebody from the Rand Corporation was brought in as consultant. Later we had a very competent research outfit, Deforest Research, work on the scientific aspects. For example, we were told that the silicone creature, the Horta, in "Devil in the Dark," could not exist under the conditions we initially created. So we changed the conditions to make possible a life form based on silicone." [This is a typo. They mean silicon, the element, not silicone, the breast implant]

Ron Barlow runs the Federation Trading Post on East 53rd Street, which sells such things as a view of the stars as seen from Vulcan (Mr. Spock's home planet) and facsimiles of Tribbles (the furry creatures featured on Star Trek's most popular episode, "The Trouble with Tribbles"). The store also sells the usual posters, buttons, and model kits.

According to Barlow, "Star Trek offered more than any other TV show. It gave a view of the future. For one thing, it said there will be a future, and it will be a lot better than the way things are now. In the future, humans have gone beyond racism and petty hatred. The major difference I can see between Star Trek and Space: 1999 is philosophy. In Star Trek all life forms are to be treated as intelligent. In a recent episode of Space: 1999 there was a monster, and all they could think of doing was killing it." [The only year 1 episode with a monster was Dragon's Domain, and it had eaten a number of crewmen before they decided to kill it]

Neil Kublan is Vice President for Research and Development of the Mego Corporation, which makes most of the Star Trek toys. "I still watch the show," he says. "I've seen every one at least three times. Both my kids watch it, and I've got a 22-year-old sister-in-law who's a Trekkie." "Why is Star Trek popular?" Kublan asks. "It has superheroes, guys that are larger than life. It has monsters, but never ones that are too frightening. It has superb characterization. Every character in it has an interesting personality. It's like a far-out Aesop's Fables. Good triumphs over evil, and nobody gets hurt. There's no blood, but a lot of ethical conduct, and fair play; not to mention good stories and great special effects."

Kublan declined to cite specific sales figures for Mego's Star Trek merchandise, but claims that every item has sold at least several hundred thousand pieces, and that the dolls have sold millions.

Space: 1999 has its partisans too. Quite understandably, Martin Landau and Barbara Bain, who star in the series, are among them. "The important asset of 1999," Landau says, "is that it's set in 1999, not 200 years in the future. My guy was born in the 1950s. He grew up with the likes of John Glenn. Space: 1999 is rooted in the present. We have taken a bunch of contemporary people and sent them flying, out of control, through space. We can't say "hey, let's go there because that looks nice." Star Trek was kind of macho in a way. They had this big ship with big weapons which could destroy planets. We're at the mercy of everyone we encounter. There's one episode where we come between two warring planets, each of which wants to use us as a military base. I find myself in the position of Henry Kissinger." [Last Enemy]

Meanwhile, the Star Trek machine rolls on. There will be a convention of believers February 12-16 at the Commodore Hotel, and Ballantine is preparing a "Star Trek Concordance" that will detail the who, what, where, when, and why of all the episodes.

According to Elyse Rosenstein, one of the organizers, the Star Trek conventions have been attended by as many as 15,000 enthusiasts. The convention (admission $16) consists of five days of panels, speeches by Star Trek actors, masquerade, fashion-designing, song and art contests with a Star Trek motif, and the expected purveying of toys, posters, and merchandise. According to Rosenstein, who is 24, "the conventions attract a very wide age-range, though mostly people who come are between the ages of 15 and 25." She feels, as do most Star Trek partisans, that the actual television program attracts a much wider audience. Some even object to the Star Trek following's being called a cult. Says D.C. Fontana, "I don't think you can include people like Isaac Asimov and the head of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and still call it a cult audience."

Finally, of course, there is the long awaited Star Trek movie. Rumours abound, and D.C. Fontana says only that the script is now in the third-draft stage, and that in it both characters and technology are eight years older.

According to rumour gathered by Ron Barlow, "in the film Kirk is an admiral, Nurse Chapel is a doctor, Uhura is communications chief for Star Fleet, and McCoy is working on a planet. They all get together again for this special mission, which has to do with the nature of God." Well, if you're going to bother to do science fiction, why fool around with mundane plots? [The film was made in 1979]

See the accompanying article by Isaac Asimov: An Expert's Verdict: 'Trek' Wins

Space: 1999 copyright ITV Studios Global Entertainment