UK Press

Radio Times

In 1994, the BBC ran a special tribute to Lew Grade (more). The BBC-owned listings magazine, the Radio Times, ran a feature in their edition for 27 August- 2 September. As part of the line-up, Space: 1999 War Games was shown on 30th August at 11:15 (or 11:45 in Wales).

In September 1994, the series X-Files arrived on British TV, and Radio Times did a "sci-fi special" feature with brief mentions of Space: 1999, in the 17-23 September edition. "The crew had trouble with inhabitants of many planets, including the critics of planet earth, and Space: 1999 became "Cancelled 1977""

In May 1998 the BBC started showing Space: 1999. On page 10 of the Radio Times for 9-15 May 1998, there was a little science fiction news section, including an Eagle photo (from the 1993 Wolverhampton exhibition, not the series).

In 1980, the BBC featured the film industry in their business documentary series The Risk Business (broadcast 9 April 1980). Presented by Michael Rodd, it included behind the scenes footage of the new Star Wars film, The Empire Strikes Back. In the Radio Times article, they also interviewed Nick Allder. Although Space; 1999 was not mentioned, there is some nice background on Allder and Bray Studios.

Nick Allder is now one of the most highly paid and most sought after special effects directors in the film industry. He is the man responsible for special effects on Alien and on the forthcoming sequel to Star Wars, The Empire Strikes Back (due to be released in Britain in May) and works, appropriately enough, at Bray Studios, once the headquarters of Hammer horror films.

Hammer films, along with the Carry On sequence and the later Confessions sagas, were the last hiccoughs in the moribund British film industry, and time was when Bray Studios echoed to the highly commercial cries of ghouls, and the fibreglass gravestones filled the lawns that run down from the studios to the river Thames. The studios still have a lowering, ominous atmosphere, from the skeletal oak that marks the end of the drive to-the untidy cluster Of Nissen huts and sound stages that cluster round the peeling belvedere of the old house.

But the activities of the studios belie their appearance. Bray Studios have taken on a new lease of life, a new identity. Now they are adjuncts of the American film industry, rented out for the filming of sequences from American pictures, and the headquarters of freelance artists like Nick Allder. In these workshops and studios are created some of the special effects key to the making of some of the most successful, and most lucrative, films the international cinema industry has ever produced.

It is a paradox, not lost on Nick Allder and people like him, that at a time when it is widely acknowledged that British technical expertise is the best in the world, and when Britain has a number of highly talented directors and actors - people like Michael Apted, Michael Lindsay Hogg, Jack Gold, Ridley Scott, Ian Holm and John Hurt, all trained and developed in British television and theatre -it is the American cinema industry which has, in the main, recognised their talent, and deployed it in films, making vast profits in the process. The British film industry, despite such reserves of expertise, remains obstinately moribund, declining, not for lack of talent, but for lack of investment.

'What we would like to see,' Nick Allder says, 'is more investment for films coming out of the city. We live on US money at present, which is fine for me and the people who work for me, but what an opportunity lost! Look at a film like Alien. It was a totally British-made film, with the exception of some American actors. It cost 9.9 million dollars to make. It leaves the country in ten cans of film - one man could carry them - and it earned between 80 and 90 million dollars within eight months of its release. Not all of that is pure profit, of course, because there are overheads, but even so, it is a huge and fast return on investment.'

It is a risk that American film companies are delighted to take, and when they do so it is invariably to British experts like Nick Allder that they turn. Special effects is a booming industry, and not just because of the current fad for sci-fi films, such as Alien, Superman, Star Wars and its sequel, all of which heavily depended for their success on special effects work done in this country. They are also needed for war films, adventure films, gangster films - any film which calls for sea battles, air battles, explosions, carnage and general mayhem.

The special effects men have become the new, hidden, stars of the film industry, and it is noticeable that in such sure-fire successes as the James Bond films, all the other formula elements have been gradually subordinated to the progressively more elaborate and breathtaking sequences that spring from the fertile brains of the special effects teams and the stuntmen.

Nick Allder has been working in special effects all his life, His father was film technician, and he spent hours as a child in his father's workshops: by the time he was nine years old he could thread a spool of film into a camera. He left secondary modern school at 16, and went straight into the film industry, working on commercials and cartoons.

But his true apprenticeship was under the late Les Bowie, the grandfather of British special effects, and one of its great technicians. (One of Bowie's last assignments was to create the flying sequences in Superman).

Bowie ran his own company, Bowie Films, which was highly successful for many years, and became one of the main training grounds for the new generation of British special effects men. But his company was affected by the general malaise in the film industry internationally in the late 1960s; it was first bought out by Shepperton Studios, and then, in 1971, closed down. Most of Bowie's recruits, including Nick Allder, then went freelance - and flourished.

By then, Allder already had years of experience. Like many others he learned his skill on Hammer horror movies - 'our bread and butter in those days, stakes through the heart, dis- integrating flesh, that sort of thing '. But he had also worked on innumerable other films, including A Man For All Seasons and Battle of Britain. Special effects in A Man For All Seasons? 'Weather,' he says succinctly. ' And the boats on the Thames. You probably thought they were being propelled by oars: they were on cables.'

Like some modern Merlin, he was becoming a wizard of fakery, gradually perfecting the bizarre expertise of the special effects man; at his command he had a repertoire of miscellaneous skills, able to create with complete realism, but without danger, explosions, fire, smoke, collapsing bridges, the gamut of gore from gushing to coagulated, tumbling buildings, disintegrating aircraft, laser-lacerated spaceships, planet landings, monsters, ghouls, vampires, a veritable Walpurgisnacht of horrors attended by whatever vagaries of weather or nature that his scriptwriter had devised.

Along the way he had gathered together a team of experts - the specialists in in flying, in pyrotechnics, engineering, in materials such as glass fibre or plastics that are the tools of the trade, and he had had to master innumerable technologies himself, keeping up-to-date with the latest developments in space hardware, aircraft, weaponry, computers, and so on, so that his effects would have absolutely modern veracity, and his techniques deploy the latest methods and materials.

The place where all this wizardry was devised resembles nothing so much as a fit-up garage off the Ball's Pond Road. Girlie calendars hang next to thick reference books on aerial warfare; the small space - perhaps 25 feet square, with an untidy gantry above - is crammed to overflowing with cables, wires, paint guns, linseed oil, batteries, wheels, clamps, blow-torches and a vast impedimenta of tools.

Slung from a high shelf is the gutted jumbo-jet model used for The Medusa Touch; hung from the gantry, with surrealist aplomb, is the headless trunk of the Ian Holm robot from Alien.

Allder relishes his wizardry, and the jiggery-fakery of his art. He delights in telling you about the new blood confections he has created, that have arterial authenticity, but that you can quite comfortably drink. He explains how, when he explodes a car, 'it's not just any old car, but one that has been specially prepared; the petrol tanks have been taken out, and the hinge-pins; the doors are fixed so they won't blow more than six feet; the explosives are precisely used for visual effect - it's only the stunt men who throw themselves on the ground, you know, when it blows. You could stand right next to one of my cars and when she went you wouldn't feel a thing.

Perhaps to date his most spectacular effects have been achieved in Ridley Scott's film. Alien. It was Allder who had the main task of creating the extraordinary sets, designed by the Swiss artist H. R. Giger, which, with their surreal marrying of industrial and organic forms, were some of the most brilliantly original film designs since Fritz Lang's Metropolis. He also had the task, among other things, of creating a robot who could be decapitated, spilling its electronic entrails in a flux of white fluids, in one of the most compelling, and horrifying, sequences in recent films, and of causing to erupt, from John Hurt's chest, one of the most perfectly disgusting monsters ever seen on the screen.

For this particular sequence, both he and director Ridley Scott kept the actors in a state of secrecy: no one except the unfortunate John Hurt was told what was going to happen. Hurt spent hours in make-up, being fitted with a false chest-piece fitted with a hydraulic. ally-operated but initially invisible rubber monster. The other actors waited nervously on set (the dining-room of the space-tanker, which was completely white) wondering why all the cameras had plastic covers over them, and all the film technicians were swathed from head to foot in waterproof overalls.

Finally, after hours of waiting, they shot the scene. Hurt emerged, looking completely normal, ate a space meal with them, and then abruptly launched into a terrifying spasm of choking and retching.. The other actors dragged him on to the table, face up, where-upon the hydraulics went into action, and his chest began visibly to pump, as if his heart were erupting through his rib cage. There was a spurt of blood, and then suddenly through the false chest-piece debouched a hideous pink embryo, toothed and shrieking at its birth, an inflatable rubberised horror created in the Allder workshops.

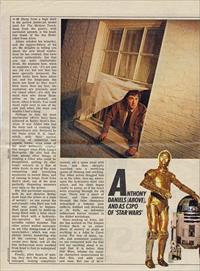

Since working on Alien, Allder has worked on The Empire Strikes Back, in an atmosphere of secrecy as acute as anything in a John le Carré novel. For fear of leaks, rip-offs, and premature publicity, no one connected with the film will say anything about it except that it is better than Star Wars, retains the familiar characters immortalised by that film, and adds some new ones. But one of his tasks was to update, and improve on, the androids, particularly those twin heroes R2D2 (now fully remote-controlled) and C3PO, the gold-suited humanoid one with the tetchy and pedantic disposition, played with aplomb by the English actor Anthony Daniels, entirely invisible, and encased from head to foot in beautiful, but extremely uncomfortable, armour-plating.

Daniels, like Allder, is someone who has benefited from American investment in English expertise, and who regrets very much the virtual non-existence of a British film industry. The unexpected, and unpredicted, success of Star Wars, which has grossed over 300 million dollars, and developed into both a cult and a mass-merchandising operation, changed his life - both, he feels, for good and for ill.

Space: 1999 copyright ITV