Trade Press

The splendour of days gone by

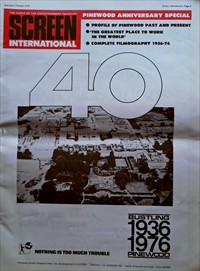

Screen International is a UK film and TV trade journal, a UK rival to Variety and Hollywood Reporter, published weekly since September 1975. In addition to news and trade adverts, the paper lists productions at different studios, including Pinewood, Elstree and on location. The October 1976 issue had a special section commemorating 60 years of Pinewood Studios, which included this article, and an advert from Space 1999

by Sue Summers, Saturday 2 October 1976

An aerial view of Pinewood, probably 1975 (it looks like snow on the ground). Heatherden Hall is front right, with the formal gardens in front, the paddock area (used for Full Circle and Matter of Balance), and the water tank left. Outside the photo, the public road is to the right, Black Park is on the left. L and M stages are top left. The newly built 007 stage, not seen beyond the top of the photo (possibly still in construction), would be used in 1976 for The Spy Who Loved Me.

Pinewood's present is inevitably peopled with ghosts of its past. Walk through the slightly faded splendour of its corridors and they stare back at you. Names in which the hopes of Britain's film-makers were once vested.

Those three leading men in the Rank stable, for instance Dirk Bogarde, Stanley Baker and Anthony Steel. Or that collection of contracted talent that Fleet Street once ironically labelled "The Charm School" - much to the resentment of its members, who included Honor Blackman, Shirley Eaton, Diana Dors, John Gregson, Maxwell Reed and Joan Collins.

Take a walk outside, to the water-tank which has been the aquatic stage for so many films and you find yourself surrounded by the rotting debris of past productions.

Pick your way among lumps of polystyrene and discarded wood and you are face to face with a lone plaster elephant, disintegrating all by itself. Not a poignant relic of Cleopatra, as you might expect, but of Ken Annakin's The Long Duel, made in 1966, the year of Fahrenheit 451, A Countess From Hong Kong, The Whisperers, Marat Sade and - what else? Carry On Screaming!.

Somehow, despite all the bustle of today, Pinewood is a place where it's easy to be nostalgic. Simply, perhaps, because it's the most beautiful of the clutch of studios that Britain still possesses, the most famous survivor in an area that once housed Beaconsfield, Walton-on-Thames, Denham and Merton Park as well as Shepperton and Bray.

Perhaps it's because Pinewood is now Britain's only fully-maintained studio, which gives it a totally different atmosphere from all the others. Or perhaps it's because its very solidity seems to stand for a time when Britain's film industry had a much surer sense of itself and its own direction.

In fact, cold scrutiny of cash considerations tends to sweep all this nostalgia by the board. It may be true that in 1948, J. Arthur Rank reported to shareholders that "the studios were fully occupied with the production of British films", but in 1949 a year when Pinewood made nine films for the Rank Organisation, including Astonished Heart, Boys In Brown and Madeleine, the Organisation lost £1,667,000 on film production alone.

Even during the war, when Pinewood, production curtailed, became an out-station of the Royal Mint, the joke went around that the studio was making money for the first time.

Heatherden Hall (1865) was extended with a studio administrative block, of which this is the main entrance, originally a 1568 fireplace from Irlam Hall in Derbyshire.

And as George Perry recalls in his new book on Pinewood, "Movies From The Mansion", there were times before the war when only the "personal cajoling" of Richard Norton, Pinewood's first managing director "induced the bank to meet the weekly wage bill."

What else is new, indeed. In the words of producer Hugh Attwooll, who has been at Pinewood more or less consistently since 1948: "Ever since I've known it, this industry has been in a state of crisis. I joined it in 1928, in the silent era and of course the first crisis was sound. Since then, I've been through a dozen at least."

"Kip" Herren, the most recently departed of Pinewood figures and its managing director for the past ten years, was determined that this supplement should not just consist of a superfluity of purple passages. It should, he said, show Pinewood "warts and all"; should not ignore the fact that the studio lost £450,000 last year or that the beginning of this year was nothing to boast about either.

Kip, as most people in the industry were aware, was a supremely realistic individual, who coupled an enormous belief in Pinewood with a very thorough knowledge of conditions in the film industry at large.

Under his aegis, Pinewood was forced to adapt to the new conditions of post-war film-making. It underwent a transformation from a place making solely Rank Organisation pictures with Rank money, to a studio competing for production in the world market-place.

Pinewood's labour force was slashed back from 1,438 to 700 permanent staff. The front office was cut back to four - a figure which Kip felt could not be bettered in terms of efficiency.

The reason Kip was brought into the studio from Shepperton was, in fact, to make these changes. One of fought very hard indeed, was the the most significant, for which he introduction of facilities for television production.

"Ten years ago, I realised that the film industry was going through a traumatic change," he told "Screen International" shortly before his death. "I realised that feature production was going to change and it was going to be harder in the future.

"I felt there was an enormous market in television and I saw no reason to look under the bed at night to see whether a television producer was lurking there. So we built J and K stages which were designed to take both feature and television production; and then L and M, which were an improvement on J and K to the point where if we had to build any more I'd just take those plans out and dust them off.

"Now we have probably the two most prestigious television series being made anywhere in the world. If we see that the content of television work is increasing and film production is decreasing, we will adapt one or two more of our stages along the L and M principle."

The most difficult decision Kip was called on to make in these days of sporadic production, was how much idle time the studio could afford to tolerate among its workforce.

If he had created redundancies, when the studio was running at less than the three productions that ensured moderate financial success, skills which had been built up over the years would have been lost.

To keep them going was expensive, despite the diversification which the studio has introduced over the years in terms of renting space to outfits like Zoom Television, running conventions and so on.

Up to now, he said, the policy had always been to accept a high level of idle time. He could not have done that without the backing of the Rank Organisation and, in particular, Sir John Davis.

It was clear from talking to Kip that he felt Sir John Davis was crucially important in keeping Pinewood open. Sir John himself tends to shrug this off, expressing an equal interest in each one of the Rank divisions, though, he adds, "It has obviously been exciting to see some of the great films that have been made there."

The reason why the Rank Organisation has supported the studio throughout the years, despite the fact that it hasn't been remunerative, is, he says, "because we believed in it."

"Some of us have always held the view, not only in running a business but in relation to other things, that you have a social responsibility as well as a financial one. We've always held this view and I don't see why it shouldn't continue.

"I suppose if you had asked us to acquire Pinewood today, it would be a different matter. But having had it in the background all this time, it's another thing.

"It has been our policy to keep it up to date. To install the latest equipment to fulfil most of the modern needs. It's the finest studio in Europe."

Whether the future policy of the Rank Organisation towards Pinewood changes with Sir John's departure in March remains to be seen.

Despite rumours that Rank is hoping to sell nearly everything in its possession, it's difficult to see what they could actually do with the studio. For one thing, it stands on Green-Belt land and cannot be redeveloped for its property value. For another, it is too large - as Kip Herren always maintained - to four-wall. And for a third, it is difficult - rumours about Arab petro-dollars apart - to imagine anyone buying it.

The only alternative, it would seem, would be to close it down completely. Kip was confident that Rank's new chief executive Harry Smith- who knows less about the film industry than Sir John - would continue to support it.

Sir John himself remains somewhat tight-lipped about what he sees as Pinewood's future. It's not his particular problem any more, he implies, adding - curiously for someone who has been on so many film industry committees himself.

"It all hinges on Sir Harold Wilson's interim action committee. Out of this will come the shape of the industry in the future, though its recommendations may take time to implement. Until the next phase of the committee is over, the uncertainty running right through the film production side of the industry and the other sides, to some extent, will continue."

Talking to film producers who work at Pinewood, one encounters almost no criticism of the studio itself.

Peter Rogers, who describes himself as "the oldest inhabitant of Pinewood, except perhaps for my wife", commends it for the efficiency of its work-force, observing rather tartly - in response to my rather woolly questions - "You come here to make a film, darling. Not to look at the rhododendrons."

Cubby Broccoli came to Pinewood in 1954, to make Hell Below Zero with Alan Ladd. Since then, he has rarely gone elsewhere. Pinewood is, he says, the home of James Bond and he'd feel it was rather sacrilegious to make Bond's home anywhere else.

"We depend on Pinewood and Pinewood sort of depends on us, speaking of the Bond syndrome. The efficiency for me starts with my own technicians. We've worked with them for years and I know all the characters. Some of them I've even outlived in the sense of retirement. Combined with a very fine group of managerial men, it's a very good team."

What Broccoli does feel rather sore about, however, is the fact that the Rank Organisation would not contribute to the cost of the vast new silent stage the largest in Europe and possibly the world which United Artists has built at Pinewood for The Spy Who Loved Me. It is, he feels, indicative of a lack of belief in the studio at the highest level within the Organisation.

"I think the confidence of the people who run the studio, exceeds the confidence of the people who own it. Which is a bit sad. In my own humble opinion, it's the last remaining leading studio in Great Britain.

"The silent stage is a great asset to Pinewood. I think it enhances the studio and we've already had a great number of queries about the use of it in the future. I was very disappointed that the Ranks themselves don't have as much confidence as we do in the studio, or else I think they could have participated in building it."

The only murmurings of discontent about the studio itself come from a younger generation of film-makers entirely. Alan Parker and Alan Marshall made their first feature film Bugsy Malone at Pinewood. Used to working in entirely different idiom - that of commercials - they found the studio "magnificent", but were impatient about the constraints it imposed upon them.

"I felt it was almost like a book- keeping exercise," says Marshall. "It was a nightmare of accounting. It was the first film with Alan in which I haven't been on the floor. "What we hated were things like having a stand-by plasterer and his assistant every day doing absolutely nothing. But you had to abide by the rules and regulations. We had one electrician who did nothing but make tea all day long. His job was to put the red light on when we were shooting and close the door, but basically he was in charge of tea.

"I think we could have lost between ten and fifteen per cent of our staff. One wondered how much we added on top of our budget by going to Pinewood instead of Shepperton which we originally budgeted for. The film cost more to make simply because we were supporting a full-time labour force."

Against this view, one could put that of John Dark, a producer who makes his films at Pinewood because, with the special effects work they require, they simply couldn't be made anywhere else.

John Dark's films, like The Land That Time Forgot, are perhaps significant of a return to heavily studio-based productions in the industry at large a fact which clearly works in Pinewood's favour.

He moved to the studio two years ago from Shepperton, because, he says, "I was standing in the car park one day and somebody put a lot number on my back and I got the message."

And he's there precisely because it's not a four-waller and has the technical equipment and know-how his productions require.

"Even when we were at Shepperton, we had to bring over Charlie Staffle and his men and all their front and back projection equipment. The big advantage is that they are here and the technicians are here, so when we are developing one of these subjects - they take a lot of pre-production work - the boys are on hand to tell us about their latest developments. We use a lot of thinking time," he said.

Dark is convinced that, for his type of picture at least, Pinewood is much cheaper than a four-wall studio.

"There are only three countries in the world where you could make these kinds of films the States, Japan and Great Britain. We are still about 50 per cent cheaper than the States.

"And the number of people making these pictures is increasing. There's Bond and the Star Wars, Space 1999, Superman and we have Harry threatening to make Micronauts - they are all special effects movies." Star Wars was filmed at Elstree, from 7 April - 16 July 1976, with some scenes in mid-May at Shepperton, and Tunisia from 22 March-4 April, plus pick-ups in the US in January 1977. In August 1975 pre-production they considered using Pinewood, but too many stages were booked by other productions including Space: 1999. Superman would start filming on 28 March 1978 at Pinewood. Micronauts, which Johnny Byrne had been attached to in 1973, would never be made.

But what of the Rank Organisation's own place in film production? That, as even a most cursory inspection of the facts shows, has continued to dwindle to a point where Rank's one reliable annual act is the financing of one more Carry On...

There are those who say that Rank's success with Bugsy Malone will encourage it to invest in more film production in the future. Others, meanwhile, say that its corporate fingers have been so badly burned in the past, that film production is about the last thing it wants to involve itself in - apart from its cinema circuit, that is. Producer Kevin Francis is one of those who would like to see Rank play a more active part in production than it has done of late.

The studio, as a facility, he says, is virtually uncriticisable. It is "the only ball-game in town" and as a studio servicing operation it's "hard to see how it could be improved".

However, he maintains that it is difficult to envisage a future for it in its present state of splendid isolation:

"Is there a British industry? I think the time has come to sort that out. Kip was clever because he attracted to the studio people with some continuity of production to base themselves here. But I think that only 75 per cent of revenue can come from rental. But if there were a production programme via an allied company...

"I'm not saying that Rank should make films just to fill the studio. But for Pinewood's losses last year, it could have made two films. The losses reflect idle time. If you filled that time with pictures, you'd have two finished pictures for the losses the studio has made."

One opponent of this view is Sir John Davis, because, he says, you cannot make films - or even film series for television, as Francis would like - in order to fill the studio. This is just one area, he feels, in which the film industry is unrealistic.

Kip Herren agreed with him: "There is no alternative for this studio but the constant grind of getting more and more work. We don't make films, but when films are being made we get the lion's share. It's not a wearing process, it's our job."

Now that job is in the hands of Ed Chilton and studio manager Cyril Howard. It was one that Herren himself saw getting progressively more difficult as time went on - the more so because of the double taxation convention with the States which is looming large and threateningly on the horizon and could keep at home the American finance on which Pinewood depends.

Taxation has already made life complicated for the studio - with Equus, for example, moving not into Pinewood where its production offices were, but from Ireland to Canada. Kip was clearly worried by these trends despite the fact that film-makers like Norman Jewison have maintained their offices at the studio while moving out of the country. His remedy was that "We'll just have to work harder to attract production."

Cyril Howard is, of course, equally aware of these problems. He is at pains to point out, however, that Kip's death has not deprived the studio of strong management.

The same thrusting, go-getting, attitude, he says, will continue. And he lists eight new productions, both large and small in size, which he hopes to see shooting at the studio- either in part or completely during the year ahead.

"Pinewood will go on, there's no question of it," he asserts. "The captain of the team may have changed but the team has to play as well as ever because there's a lot of people's livelihood depending on it.

"They've been shooting us down for such a long time that one gets used to hearing rumours. But who has been proved right? I think we're winning."

Space: 1999 copyright ITV Studios Global Entertainment