Press

1975 Smash

Newsweek is a weekly US news magazine based, running since 1933. In addition to the standard US edition, there was a separate "international" edition with different covers and more European content.

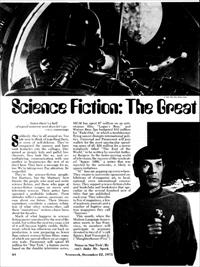

by Peter S. Prescott

US edition p68-74

International edition, cover by Randy Weidner features a Space: 1999 astronaut (in white), and a stylised Eagle with fins, p44-49

Suddenly, they're all around us. Too late now to think of repelling them, or even of self-defense. They've conquered the nursery and have sunk tentacles into the colleges. Disguised as pimply kids and pallid biochemists, they look like us, and are multiplying, communicating with one another in frequencies the rest of us don't hear. They have a message for us, too: We're taking over. Pay attention. Be respectful.

They're the science-fiction people. Not Martians, but the Martians' best friends: the people who read and write science fiction, and those who gape at science-fiction images on movie and television screens. Their antics have spawned a profitable industry. Their attitudes reflect a narrow, necessary unease about our future. Their literary aspirations constitute a curious refutation of what other writers-they call them "mainstream" writers-have been about for decades.

Much of what happens in science fiction passes unnoticed by the rest of the world, but within the next two years a lot of it will become highly visible. Hollywood, which has otherwise cut back on production, is now preparing no fewer than sixteen science-fiction films, many of which use special effects on an expensive scale. Paramount will spend $5 million for Star Trek, a feature movie based on the durable television series; MGM has spent $7 million on an anti-utopian film, Logan's Run, and Warner Bros. has budgeted $10 million for Fade-Out, in which a troublesome flying saucer disrupts international politics. Universal and Paramount will join wallets for the most spectacular spending spree of all: $20 million for a movie tentatively titled The End of the World, to be written by novelist Anthony Burgess. In the faster-moving world of television, the success of the syndicated Space: 1999, a series that was rejected by the networks, is likely to spawn imitations.

"Sf" fans are popping up everywhere. They swarm to university-sponsored exhibitions of sf-magazine art, to local, national, even international conventions. They support science-fiction clubs and bookclubs and bookstores that specialize in the several hundred new sf titles that are published each year. They subscribe to five sf magazines, a few sf academic journals and a number of fugitive amateur magazines they call "fanzines."

This month, when the Modern Language Association meets in San Francisco, its members will participate in seminars devoted to two of sf's cult figures, Kurt Vonnegut Jr. (Slaughterhouse-Five) and Robert A. Heinlein (Stranger in a Strange Land), and two of its most respected newer writers, Ursula K. Le Guin and Robert Silverberg. The teachers will then disperse to offer, in colleges from Barnard to Eastern New Mexico University, more than 1,000 courses in science fiction, and countless more in high schools and grade schools.

What is science fiction? Within the family, attempts at definitions are part of the game. Heinlein prefers "speculative fiction", which others have picked up, but it's too vague and encourages fans who insist that most great writers are sf writers (the brotherhood has claimed, among others, Homer, Plato, More, Swift, Defoe, Borges and Nabokov). Damon Knight, a writer and editor of sf anthologies, has suggested that sciencefiction writers, like Gnostics, alchemists and depth psychologists before them, keep in touch with man's unconscious. It's a good claim, a nonliterary claim, but it's not often heard. In brief, science fiction is a kind of fantasy that is rhetorically based on technology, either real or imaginary, or is based on a plausible extrapolation from present reality. What explains its current vogue? Science fiction is entering a boom period now, says Norman Spinrad, one of the better sf writers, "because in an absolute way it's inherently the literature of the times. You can't really deal with the times without writing science fiction.. You have to have a future perspective."

...

The science fiction available today may be divided roughly into four categories. Each has its own fans who are often scornful of the games being played in the other three stadiums. Two of the four, the heavy-money categories, are produced by television and Hollywood. The less affluent two are literary: one is the traditional space-opera story; the other, more restive, yearns for recognition as art.

Star Trek is more than a television series that died and was resurrected from the vault; it's a way of life. Today Star Trek thrives better on reruns than it did during its first incarnation, 79 episodes produced between 1966 and 1969. Today, children not born when the program was first shown nationally on NBC hold Star Trek parties. There are Star Trek stores in California and New York that sell foam-rubber Vulcan ear tips and buttons announcing "I'm Scanning Your Body." In a forthcoming book, actor Leonard Nimoy admits that he has difficulty dissociating himself from the role of the imperturbable Mr. Spock that he played in the series. As many as 18,000 "Trekkies" have assembled at their own conventions. At Memphis State, East Texas State and Lewis and Clark College in Oregon, seminars are offered in "The Philosophy of Star Trek."

Star Trek jellifies the mind. It began with some scientific playfulness, but as budgets and imagination shrivelled, the shows became more "realistic." In theory, the starship Enterprise glides about the universe, its mission "to boldly go where no man has gone before," but more precisely to impose mid-twentieth-century American democratic ideas on alien civilizations. In one episode, the Enterprise comes upon a planet run like a Southern plantation: the white folks live in the clouds savouring art while the dark folks work in the mines below, prevented by an invisible gas from attaining full humanity. The boys from the Enterprise straighten that out, you may believe.

Space: 1999, this season's surprise success on local channels, is nearly as stupid as Star Trek, but much prettier. There's Martin Landau, whose stare will pierce concrete, and Barbara Bain, whose face seems frozen by Novocain, and there are Brian Johnson's special effects, which are indistinguishable from those he helped create for Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey. In sf television, innovation is to be avoided at all costs. The series is about our moon, which breaks loose from its orbit to go adventuring in space. Colonists based on the moon are soon coping with emergencies around the universe. Rudi Gernreich, who gave us topless bathing suits, designed the moonmen's costumes. Recently, Landau, in a white suit, faced down an evil alien in a black suit with flaring cuffs. All that was missing was high noon in Tombstone-but Westerns are dusty and sweaty and this is a clean and pretty show.

Other movie men are doubtful about using a lot of hardware. Brian De Palma, who will direct Carrie, a film about a telekinetic teen-age girl, believes "science fiction in the movies is the hardest form to make work. Audiences want to get emotionally involved with the characters. Too many science-fiction films are plot-device and special-effect movies rather than people movies."

"We don't do spaceships unless we're prepared either to spend $20 million or do a B movie," says producer Si Litvinoff. "Everybody seems to be spending a lot of time on the look of things rather than on the ideas of the best writers on what things will be like. If you take a good notion and pursue it and stop worrying about the hardware, you're going to be successful." The good notion that Litvinoff is pursuing just now is a space drama with music, The Man Who Fell to Earth, starring the androgynous David Bowie as a superior being from another planet who is stranded on earth and teased by the natives for being different. Fortunately, the fellow is a philosopher: "I suppose we would have done the same thing to you if you'd come to our planet," he reportedly concedes.

Less intellectual, perhaps, will be The Star Wars, a $9 million movie about a juvenile gang rumble against Fascist oppressors of the galaxy. Its director, George Lucas, who made American Graffiti and the futuristic THX 1138, doesn't care if it's called science fiction or not. "A shoot-'em-up with ray guns," is his description. "A romantic fantasy about as serious as a spaghetti Western. A sword-and-sorcery film." Steven Spielberg of Jaws will direct Close Encounters of the Third Kind, which producer Julia Phillips says will be "the 'Jaws' of science-fiction movies."

Even if all these films fail, it is certain that there will be others. "Forty per cent of the scripts I've been getting a look at in the last few months are sf," says "Logan s" director, Michael Anderson. "That's compared to zero two years ago. It's the Western of the future. That's what we all feel here."

For all its hardware, visual science fiction is severely limited in its effects. The joy of written science fiction lies in the abstract and sometimes exceedingly complex intellectual premises with which it is wholly concerned. The Golden Age of Science Fiction began in 1939, the year Asimov, Heinlein, A.E. van Vogt and Theodore Sturgeon began sending stories to Astounding Science Fiction's new editor, John W. Campbell.

Space: 1999 copyright ITV Studios Global Entertainment