Interviews

The Master of Space

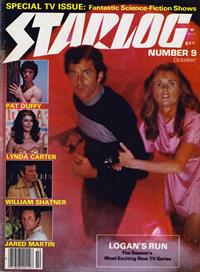

STARLOG INTERVIEW

Talking about his career and the future of science-fiction television: "... The possibilities are limitless."

By ED NAHA

Starlog #9, Oct 1977 p30-33

The office of TV science-fiction producer Gerry Anderson seems to be a contradiction in terms. The headquarters of the creator of Space: 1999, UFO, Thunderbirds and Fireball XL5 is tastefully furnished in an old-fashioned, almost antique manner; not a futuristic trace to be found. Located at EMI Studios, some twenty miles outside of London, Anderson's lair is littered with various plaques and letters from famous fans. "We haven't been here very long" explains Kate Curry, Anderson's secretary of three years. "We moved here from Pinewood Studios after Space: 1999 shut down. EMI is a smaller studio but it's very friendly, quite nice." She moves across the office toward a wall. "Here's something you should see."

She points to a framed letter addressed to Space: 1999 special-effects wizard Brian Johnson from the assistant editor of Science Digest. "As you might have heard," the letter states, "Space: 1999 has caused a considerable upheaval among sci-fi addicts and scientists, too. I've received some blistering' letters criticizing the scientific plausibility of Space. Many people were indignant that I expressed the view that the premise might not be that far-fetched; including several PHDs, sci-fi writers and a host of fanatic Star Trekkies ... All things notwithstanding, it's obvious that Space: 1999 has caused something of a sensation here and the applause for the special effects has been unanimous." The letter concludes on a glowing note, and it'? quite apparent by Ms. Curry's altitude that the era of Space: 1999 was indeed a wondrous one within the confines of Anderson's office.

Anderson himself breezes into the room seconds later, apologizing for being ten minutes late and radiating an aura of low-keyed intensity. A tall, soft-spoken man in his late forties, Anderson is a virtual well of phantasmagoric information and memories (after all, he DID invent Supermarionation). He is a perfectionist and takes great pains not to be misunderstood. He constantly peppers his conversation with hesitant phrases. "I don't mean to sound pompous, because I'm not that type of person," he blurts out while making a point. It jolts one to think that this quiet, precise personality has spawned nearly a dozen futuristic series in less than two decades.

Anderson gradually warms to the difficult task of being interviewed when questioned about a framed letter from astronaut James Lovell hanging on a nearby wall. "Ahh, that's my most favourite story," he chuckles. "I come off very badly in it, but I don't mind because it's true." Without too much prodding, he recounts his first meeting with a real-life space traveller in a crowded New York hotel restaurant. Space: 1999 had just made its debut and the two strangers found themselves standing at the entranceway, awaiting a turn at the breakfast table.

"We were both waiting when the head-waiter told us that if we were in a hurry and didn't mind sitting together, he could get us a place immediately. Neither one of us objected and we sat down to order. I attempted to have ham and eggs but got confused (they do eggs so many different ways in the States!) and we began to chat. He told me he was in the tugboat line and I told him I was a film producer. He asked me what I produced. 'Well, I said, 'I don't think you would have seen it because it only went on the air three weeks ago, but I have a show called Space: 1999. '

" 'Oh, I've seen it,' he smiled. 'Great hardware.' I was very pleased by that, of course, and I then told him that I had actually been to Cape Kennedy for a day. I proceeded to describe the vehicle assembly building, the launch pads for the Apollo craft and went on to tell him how I wanted to film the first American Moon journey but that, so far, no one was interested in the project. I mentioned that this surprised me because it obviously was the greatest enterprise ever undertaken by man. He listened to the whole thing politely. Finally, he said, 'Oddly enough, I used to work at Cape Kennedy myself.'

"I assumed that he was a guy that worked a computer somewhere. But I was interested nonetheless. 'I've never seen a launching. I began, 'Have you?'

'No,' he said, "I didn't see a launch but I was present during two. I didn't actually see them, though.'

I assumed he was in an underground bunker. We finished our chat, exchanged cards shook hands and parted. As he was walking out, I glanced at his card and it said 'Captain James Lovell.' I yelled out across the restaurant 'APOLLO 13!'

He turned around and called 'That's right.' I was flabbergasted and quite embarrassed. He was the guy on that terrifying trip where the oxygen tanks blew up and he almost didn't get back. We've become friends since that meeting."

Gerry Anderson is a man who is obviously interested in the exploration of space. "I think that science fiction is very important," he says softly. "It's a vital art form inasmuch as whatever progress we make in this work initially has to be triggered by the dreamer. Some time ago, people must have stood on a river bank and thought 'I wonder what's on the other side?' Then, someone came up with the idea of cutting down a tree and crossing over. But someone had to inspire him to do that. So, I think that in terms of future technology, if one can fire the minds of young people using science fiction,then, in a way, one is linked with progress that takes place some years later. SF serves as inspiration. That's from a technical point of view, but one of the other vital functions of science fiction is making people aware that we are only little specks in the universe. It gives people some idea of the enormity of it all."

He smiles slightly. "It always staggers me how few people can appreciate what a giant creation the universe is. Oh, another reason science fiction is an important medium to work in is that by putting words into the mouths of aliens, you can say some pretty useful things without actually preaching or being accused of playing god."

For Gerry Anderson, science fiction is a way of life. Oddly enough, however, Anderson did not actually start his professional career in the SF field. "I was a film technician in the cutting room, he recalls. "I became a sound editor and then, when commercial television started in England, I formed my own production company." He winces good-naturedly over that experience. "The capital was five hundred pounds (a smidge over one thousand dollars) with three partners. We did the usual thing of taking an office, buying a typewriter, printing up letterhead and all that stuff. We then sat around waiting for someone to call and say * Please will you handle the re-make of Ben Hur?' In fact, nothing happened.

"We were on the verge of bankruptcy when someone came along and asked if we would make a television series using puppets. Frankly, the thought horrified me. But because we were hungry, we said yes. And so, I made my first production in 1956." The show, The Adventures of Twizzle, was a resounding success and Anderson unwittingly began pioneering the field of television miniatures. "Because I was anxious to prove to the industry that I could make conventional pictures," Anderson muses, "we tried to make the puppet show more interesting. As a result, we were handed ... another puppet show, Torchy The Battery Boy. By this time, we had made considerable progress in the puppet area and I decided to make my own show in 1958, 4 Feather Falls. It was a puppet western which was enormously popular here."

It was at this period that the shadow of science fiction entered unexpectedly into the string-laden world of Gerry Anderson. "The marionette shows were very successful," he recalls. "We could get the puppets to do most things convincingly but we just couldn't get them to walk realistically. So, I thought, if we went into science fiction where people were riding around in super vehicles and travelling along moving walkways, we would be able to overcome that problem. So, I created a series called Supercar in 1959 and that was my first show to be distributed in America. It went out to about sixty stations, which was quite good in those days."

Although some Space: 1999 boosters may be disappointed at the reasoning behind Anderson's initial entrance into the SF realm, he is quick to point out: "I know I'm making it sound that the only reason I got into the field was for practicality's sake. But I suppose that if I hadn't had a science fiction mind in the first place, the idea never would have occurred to me. I think that, in a way, I was destined to go into science fiction. I am desperately interested in aerospace."

Anderson takes a folder from a nearby drawer which lists all the vital information available on his special effects-laden productions. With the facts in front of him, he rattles off the litany of Lilliputian wonders quite casually. "Now," he laughs, "I kind of got stuck in this area because the shows were going from success to success and I kept on getting new shows to make. Supercar was followed in 1961 by Fireball XL5 which was shown on NBC on Saturday mornings. Stingray was 1962-63 and also had considerable exposure in America. Then, I made a one hour show called Thunderbirds, which was 1964-66. This show made something of television history in that all three networks made a bid for it. But, for various corporate reasons, none of them wound up with it and we went into syndication. It's interesting that it's still so fondly remembered in the States because I've been thinking, not of remaking Thunderbirds, because I don't own the rights, but of creating a new, similar show."

He returns to the file. "I went on to Captain Scarlet in 1967; Joe 90 was in 1969. The Secret Service was never shown in America. It was at this point that I got my first break to work with live actors. I made UFO in 1969."

The fanciful series, which pitted Commander Ed Straker and the forces of SHADO against evil on-comers from deep space, lasted but one season. Oddly enough, though, it was the popularity of Anderson's puppet characters which forced him into dealing with living, breathing ones. "I hadn't realized it at the time," Anderson now laughs, "but I was creating immortals for television. Because I was making puppet shows which did not take the camera outside the studio, these shows did not date. There were no cars that would give away the time period in which it was shot; no stars that would suddenly look younger on the screen and therefore make the product look old. My shows were being repeated and repeated, over and over again. They were timeless. It got to the point we had virtually saturated the market with our own re-runs. And, so, at this point,- we realized that we couldn't continue in that area for the time being so we decided to try live action."

Although it was short-lived, UFO did successfully manage to combine Anderson's trademark of superb miniature effects with live action. It also served to give the producer a taste of action adventure which he quickly put to good use. After the sad demise of SHADO and company, he went on to film some 52 episodes of the Robert Vaughn thriller, The Protectors, before turning in 1973 to the plum of his career, Space: 1999. From the outset, Space: 1999 was a cause celebre in both the science fiction realm and the TV world at large. A syndicated show refused by all three networks, it constantly trounced them in local rating wars. A storm of controversy arose in the SF community. Was it plausible? Was it art? Was it as good as Star Trek? Was it fair to compare the two shows?

In spite of its phenomenal success, Space was given a drastic face-lift during its second season. Koenig and Helena watched some key crew members jettisoned in favour of such personalities as Science Officer Maya and First Officer Tony Verdeschi. Then, without warning and while it was seemingly still in full flower, Space: 1999 was abruptly cancelled by its distributor, ITC. What was the reasoning behind such a bizarre move?

Anderson, obviously unhappy about the death of his brainchild, shrugs wistfully. "I am going to be very cautious because I don't want to injure any innocent parties," he begins. "I think you know that the film business is split into two factions: you have the financial and the distribution side, and then, you have the so-called creative people such as myself." Obviously the problems with Space centred on this division, but Gerry discreetly backs out of fixing the blame. "Unfortunately, I cannot really tell you why the show was cancelled. England is a long way from the United States. I haven't been able to follow the show's progress. I haven't had as much information about the show as I would have liked to have had. And so, I am unable to make an assessment. I had assumed that it was due to ratings."

Listening to Gerry Anderson talk about his gradual estrangement from his own creation conjures up similarly chilling tales of corporate dementia from the Star Trek era. He talks quite frankly about the problems which arose during its first season. In a strange chain of events, Space: 1999 was simultaneously, hailed as a one hundred per cent success throughout America and at the same time termed "too weak" for the taste of the market it was taking by storm. Thus, the new faces on Moonbase Alpha appeared. "The changes were made on the advice we had from ITC in the States," Anderson offers. "They were pumping back feedback from, presumably, the station buyers and the American mail. I had no direct access to it so, obviously, I took their word."

Anderson won't actually comment on whether he was in favour of the changes or whether he feels they affected the show's popularity, but states: "This is only a gut reaction, but I would say that the more serious minded science-fiction fan preferred the first year. However, I think the higher proportion of letters I've received preferred the second."

Apparently, Anderson is still bothered by the dozens of questions left unanswered but, true to his gentlemanly nature, refuses to indulge in mudslinging. "Look," he points out. "I think that if, as a producer, you do exactly what you want to do, it can be said that you're a strong personality and you know exactly where you're going. Equally, it can be said that you're pigheaded and are totally ignoring the advice of the people who know the market. I decided that, since I was not in America, I really should take the advice of the people who were there on a day-to-day basis." In a mood of low keyed frustration, he summarizes bluntly, "I don't think either the first year or the second year is necessarily the type of show I would like to make if I were left to my own devices."

Brushing aside the more negative aspects of the aborted Moonbase mission, Anderson recounts the origins of the show, inadvertently revealing the amount of compromise that existed in the format from the outset. "When I was asked to produce Space initially," he states, "I was told that American audiences liked to see shows where Earth people are constantly meeting aliens and going from planet to planet. I didn't want to copy Star Trek. At the time, I had been toying with the idea of doing a series about a Moon base which, looking to the near future, is very feasible. And so, I presented a format which initially dealt with life on the Moon. And the criticism I received from the States was this: if we proceeded with the show, it wouldn't be long before the writers started taking us back to Earth ... which isn't what the States wanted. So, I had to find a way of making that impossible."

The producer laughs, recalling the seemingly Herculean feat of isolating the Moon. "Taking into account the current problems of disposing of nuclear waste, it seemed to me that the Moon might be a good place to store the stuff. And, if there was an accident and if the velocity was to be increased as the result of such an explosion, the Moon would go off on a rampant trajectory which would mean that, unlike the crew of the Enterprise, our people would never know where they were going to go next. It would not be a controlled flight. In fact, it would be a decidedly OUT of control flight. Very adventuresome, that."

To bring the adventuresome aspect of Space: 1999 to the screen, Anderson enlisted the aid of special-effects wizard Brian Johnson - whose sense of space-age super-heroics successfully blasted Moonbase Alpha off its course and into the perils of deep space. But difficulties arose, even with the effects: "We had so many problems," Anderson remembers. "With special effects, the terror we always live with is having a major accident. Thank God we've never had one; but it's been damn hard work.

"When we first started filming Space: 1999, we had a horrendous situation in the financial sense. We shot six weeks of effects without getting one shot in the can. Every day when we went to screen the dailies, the density of the image was in constant fluctuation. Under normal circumstances, this is a problem that can be tracked down quickly. But we just could not discover the cause of it. We changed cameras. We changed lenses. We changed power supplies. We called in experts from Eastman Kodak. We called in camera engineers. We had daily conferences trying to find out what the trouble was. We even used different film stocks. Then, we shot in black and white instead of colour. Nothing worked. We lost everything. Finally we found out it was a very simple fault. It was a brake on one of the film magazines which was dragging. Every time it dragged, it slowed down the transport mechanism, thus increasing the exposure. It was a minute problem but we lost thousands and thousands and thousands of pounds."

Anderson heaves a sigh and ends the conversation on Space. For all practical purposes, it is a lost cause- for Gerry Anderson, at any rate. Not owning the rights, he is no longer connected with it in any way, shape or form. For the veteran producer, the most heartening result of the impromptu cancellation has been the enormous amount of fan mail from the U.S. "Many people even telephone," he chuckles. "They set their alarm clocks for the middle of the night to get their calls through. One of the fans sent me a copy of STARLOG recently; the one with the articles on UFO and Space: 1999. It's a very good magazine and I'm very grateful it exists. It's a great help to the fans who are widely scattered across the States. It unites them, informs them. There is a very real need for a magazine like STARLOG. If I didn't believe that, I wouldn't be sitting here now, talking."

Anderson flashes a quick smile when subsequently asked about his move to EMI Studios. What does the future hold for the SF master from across the Atlantic? Gerry is fairly cryptic on this subject, allowing only tantalizing hints to make their way into the conversation. "At the moment," he says mysteriously, "I'm setting up production at EMI. I really just finished up Space a few weeks ago. I DO have a new project under my hat but, at this point, I'd like to speak very carefully because I don't want to spoil my chances. There is an American network interested in a NEW science fiction show. And I think that the interest is there because the intense fan activity of Star Trek and Space: 1999 has proven that there is a loyal audience wanting this kind of show. And while we in England have a profound respect for American shows (one has only to look at Star Trekk and the enormous success it has had), economically, it simply costs too much to make an SF show packed with special effects in America at this time. So the networks are now looking to me to make a new show."

Anderson becomes more and more ambiguous as he discusses his forthcoming series. "I do have a definite premise but I would hate to expose it. I only say that because I've had one or two good ideas whistled away from me and that would be a shame. It's now a question of examining how a new show could be made in England that would incorporate all the ingredients that would make it ideal for American audiences."

Besides some very real plans for television, Anderson expresses a desire to make the quantum jump to the silver screen with his futuristic adventures. "I would love to make theatrical films," he confesses. "In fact, I have made one. It was called Journey To The Far Side Of The Sun." (When informed that the film was enjoyed by this reporter, he laughs. "That makes two people who liked it. My mother, and now, you!") "One of the problems I'm up against in the motion picture field is that the second I talk about theatrical films, the first comment I get from distributors is 'Oh, but aren't you in television?' It's a shame because the effects we did on 1999, for instance, show up beautifully on the big screen. They look better on the big screen, in fact. I would very definitely like to do a full length motion picture but until that time, I have television."

Anderson really doesn't mind confining his flights of fancy to the video airwaves, though. He hastens to point out the advantages of that medium as well as the shortcomings. "I think that all filmmakers find television a little, restricting inasmuch as one cannot put across spectacle on the small screen. Making up for that, however, you do manage to gain entry into countless homes and that puts you in a very privileged position. The ideas you can get across to that audience ... the possibilities are limitless."

And so, the undercurrent of frenzied futuristic activity continues in the world of Gerry Anderson. In spite of corporate decisions, heavy doses of network lunacy and an ocean separating the creator from his audience, Anderson continues to dream ... and doggedly attempts to transform those dreams into visual brain-teasers.

Television, puppetry, feature films; it seems that there is no limit to this science-fiction devotee's imagination. "I'm working with a rock-and-roll band at the moment," he adds as a casual afterthought. "I have a label interested here in England. The whole idea would be to combine good, strong rock with some key science-fiction concepts ..." He stops in mid-sentence and smiles to himself. "Oh well, I just thought I'd toss that idea out to you. Just in case you come across anyone that would be interested in it during the course of your travels."

Anderson chuckles delightedly as he conjures up visions of future Led Zeppelins garbed in extraterrestrial gear, enacting swashbuckling space operas on stage. It is clear from the delighted expression on the producer's face that, for him, the world of science fiction is one that can stretch anywhere, in any form at any time. And, if Anderson has his way, it will do just that.