Clapperboard

The long running children's television programme Clapperboard ran for nearly 500 episodes, from 1972 to 1982. Presented by Chris Kelly, it was made by Granada for the ITV network, for the after-school children's timeslot. Although aimed at children, it was a serious and often very interesting look behind the scenes of film and film history.

The edition nationally networked at 4.25 pm on Monday 13 October 1975 interviewed with Gerry Anderson on the set of Main Mission, first in front of the computers, then sitting in Eagle chairs by the desks. There was a discussion of the puppet techniques of Four Feather Falls, Supercar, Stingray and Thunderbirds, with supporting clips. Gerry showed his puppet of Parker to explain how the puppets were operated. Then Chris Kelly talked to Martin Bower, again in front of the Main Mission computers with a selection of his replica models- Supercar, Fireball XL5, Stingray, Thunderbird 1, Sky 1 (from UFO) and an Eagle.

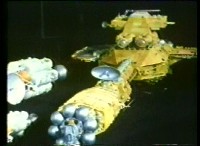

The second half, a week later on 20 October 1975, was an interview with Brian Johnson at Bray. A number of large models stood in front of them, including the Moon, three sizes of Eagle, three sizes of Ultra Probe (from Dragon's Domain), and the battlecruiser from The Last Enemy. Gerry appeared at the start and end of the programme (explaining about the filming of the Thunderbirds episode Attack of the Alligators, with a clip from the episode). In the London area only, the two programmes were repeated on Saturday 14th May 1977 at 10am, and on Saturday 21st May 1977 at 10.05am. See the TV Times listing. The two parts were included as an extra on the 2005 Network DVD Year One boxset. The original film no longer exists in the Granada archive, so a video copy was used in edited form (38m56s), using the Space 1999 theme to replace the original title music because of music rights issues.

Below are edited extracts from the interviews. The full programme is available on the Network DVDs and Blu-ray.

Chris Kelly: A tricky moment there from the new television feature Space: 1999. Fortunately things on the Moonbase have calmed down a bit now. Which is just as well as I've come to Pinewood Studios not far from London to talk to the creator of this series, Gerry Anderson. He's also masterminded series such as Fireball XL5, Supercar, Thunderbirds, UFO and many more. Gerry, on a deserted Moonbase, it's nice to see a fellow human being. Come and join me. In Space: 1999 we're asked to believe that a nuclear dump on the moon explodes and the moon is forced out of the Earth's orbit. How likely is that?

Gerry Anderson: I don't think there are many people who could really answer that question. I think the important thing in science fiction is that one has to take a certain amount of license. Nuclear waste is a problem today, and I think it will be more of a problem in 1999. We said that a good place to dump the waste would be on the far side of the moon. I think it's possible that as new materials are used there could be interactions which nobody thought about. Yes, I think it's possible.

Chris Kelly: How much research do you do into science possibilities?

Gerry Anderson: We don't do too much research. I've always made a point of this, because if you consult the experts, then you're dealing with present day knowledge. I find that somewhat inhibiting. If you take the case of Concorde, a hundred years ago I'm sure scientists would have said it was quite impossible to sit in an airplane eating caviar travelling at a speed which something like the muzzle velocity of a rifle bullet.

Chris Kelly: Gerry, you've come a awful long way from Four Feather Falls to Space 1999, and people have replaced puppets in your pictures. Do you see a day when you'll get out of special effects films altogether?

Gerry Anderson: I spent many years predicting the future, but on this occasion I'm not going to do it. I don't know what the future holds.

Chris Kelly: Well here is Stingray, one of the many made in different sizes for the programme by Gerry's team of modellers, one of whom, Martin Bower here, joined the outfit in a rather extraordinary way. Tell me about it.

Martin Bower: Well, I started making models at about 8 years old, when Gerry Anderson brought out a series called Supercar. He made Fireball XL5 and went on to other series. I kept up with him, making models of them, just as a hobby.

Chris Kelly: How old were you when you made this?

Martin Bower: I made this one more recently, actually, as I got better making models. The Fireball XL5 was made about 8 years ago.

Chris Kelly: Made of what?

Martin Bower: They're mostly made of wood, hardwood. Depends how big the model is. If the model is very heavy, I turn to fibreglass instead and using moulding methods to make the models.

Chris Kelly: Did you send these to Gerry Anderson?

Martin Bower: No. I wrote letter to him about 2 years ago. I took a lot of photographs of all the models that I make. I sent these to him, and I got a letter back almost immediately saying would I like to meet his special effects director, which I did. I started making models for the series from that time.

Chris Kelly: So what was the first series you worked on?

Martin Bower: Space: 1999

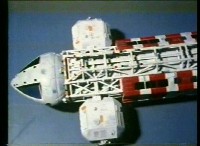

Chris Kelly: Which brings us rather handily to the Eagle Transporter, which I must say is a beautiful model. It's solid and utterly convincing. How long did it take you to make that?

Martin Bower: In actual hours, about a hundred hours. There's a great deal of work in that particular model because of the immense amount of girder work, all made of brass tubing.

Bower's replica 22 inch Eagle. It was eventually seen in some publicity photos for Bringers Of Wonder, about a year later in 1976, but it was never actually used in the series.

Chris Kelly: Why does it need to be brass?

Martin Bower: Because the centre section can drop out and the craft can fly without that. It wouldn't be strong enough; it would bow in the middle. The jets are made of aluminium turned up on the lathe.

Chris Kelly (points to the "windows" on the top of the rescue pod): Is that real glass inside?

Martin Bower: No, that's perspex. The pod, these side sections are all made of perspex. With a fibreglass nose.

Chris Kelly: The shape of things to come, as seen in the new television series Space 1999, masterminded by Gerry Anderson here. We met Gerry at his Pinewood headquarters last week. This week he's brought us to Bray Studios near Windsor to meet his special effects man, Brian Johnson. Gerry, how did your association with Brian begin?

Gerry Anderson: It was about 12 years ago that we first worked together, on Fireball XL5. Since then we've worked together on a number of occasions.

Chris Kelly: Brian, how did you get into this business?

Brian Johnson: Like all film technicians, you have to start off at the bottom, you sweep the floors, you become a very low level camera assistant. I worked for a TV commercial company, then I went into the air force, When I came out of the air force, someone offered me a job as a special effects camera assistant, and I took it up from there. That was in 1961.

Chris Kelly: Special effects is one thing, making detailed models is another. Is this a skill you've always had?

Brian Johnson: I must confess I don't really make the models. I design them, I detail them, but I get somebody else to do the hard work.

Chris Kelly: This is the Eagle transporter. This has never been built in reality; where did you get the inspiration for that?

Brian Johnson: One reads the scripts and one forms ideas in one's mind over a period of a few weeks.

Chris Kelly: Why did you give it a head that looks like an insect?

Brian Johnson: Because if you look at all aircraft, all rockets, they look like insects of one form or another. I was thumbing through some nature magazines, and I saw the head of this grasshopper. It all happened from there really.

Chris Kelly: Why so many models of the same vehicle?

Brian Johnson: Because some of the shots are long shots, and we only have a limited amount of space on the stage. So if we have this large 44 inch model, and we want it to look a long way away, we use this one the same distance.

Chris Kelly: Where do you get the odds and ends, the bits and pieces?

Brian Johnson: They're plastic kits.

Chris Kelly: They're terrifically weighty. Why are they so bulky?

Brian Johnson: The framework on this one is brass. It has to be very strong because in a number of episodes it crashed. We actually run it along cables and drop it to the ground at quite high speed. They're built very strongly and survive the series.

Chris Kelly: How do you suspend them for film?

Brian Johnson: Some of them are suspended on wires, but basically they're suspended on poles covered in black velvet. You can see there's a hole at the end there, and others at the bottom. Lighting is the key really to making the models look as realistic as possible.

Chris Kelly: In the show the Eagle comes up on a hydraulic lift. How is that operated?

Brian Johnson: We had a hydraulic dolly that we connected underneath the set.

Chris Kelly: When you say dolly, can you explain?

Brian Johnson: It's a device used for moving cameras about. The one that I use is quite old, but the hydraulic mechanism is very good and very smooth, so we get a very good scale lifting effect for this 44 inch Eagle.

Chris Kelly: What about the effect you achieve with the sky almost full of Eagles?

Brian Johnson: That's done by a very old technique called multiple exposure. One takes a model such as this, you shoot it once against the black velvet to get one image on screen. You wind back to the beginning of the shot, put it in a different position and so on and so on. One of the shots we did with 11 exposures of the single Eagle.

Chris Kelly: How big a team do you need to make all these things?

Brian Johnson: We have 3 people who construct all the models. The whole team including the camera crew is about 14 people.

The Deltan battlecruiser from Last Enemy is shown in detail with several long pans. A lengthy clip of the doomsday bomber in War Games was also shown.

Chris Kelly: How do you cope with explosions?

Brian Johnson: You have to shoot at very high speed to slow down the bang so you get a scale explosion effect.

Chris Kelly: Is there enough work of this sort in the British film industry today.

Brian Johnson: One combines it with live action effects. We don't only do model effects, we try to do the whole range.

Chris Kelly: One thing we haven't mentioned is the moon behind us. How accurate is that?

Brian Johnson: It isn't really accurate, but when it's carefully lit the effect is of the moon. Nobody really questions it.

Chris Kelly: How do you make the spacecraft appear to move?

Brian Johnson: One doesn't actually move the spacecraft, we track the camera in the opposite way. If you want the spacecraft to fly towards you, you suspend it against black velvet, and then track the camera into the model. When you see it on the screen the model appears in the distance and flies to the camera.

Gerry Anderson joins them

Chris Kelly: Have you between you ever had any disasters with special effects?

Brian Johnson: (Smiles) No, no special effects man ever has a disaster.

Gerry Anderson: No, good special effects men don't have disasters, I agree.

Space: 1999 copyright ITV Studios Global Entertainment