Student Film

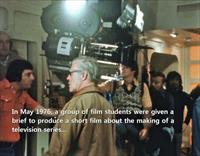

On 28th February 1976, Warwick Student Television wrote to Gerry Anderson at Pinewood proposing to do a documentary on Space: 1999. "We would like to show how and where the series is made, talk to the people who made the films, and to the stars of the show, Martin Landau and Barbara Bain, who help to make the series so successful." Warwick Student Television was operated by students at Warwick University, in Coventry, and produced films for student television stations in Britain.

In 2014, at the Anderson convention, Network showed the student film. It appears on the Network Second Series DVD and Blu-ray (2015). It is 25 minutes, 8 seconds long.

It was filmed on two days. The scenes from Mark of Archanon would be around May 6th or 7th; the scenes from New Adam, New Eve would be around June 2nd or 3rd. Keith Wilson was filmed on the New Earth set from New Adam, New Eve; it is impossible to tell when the other interviews were conducted. Half a day was spent at the SFX studio at Bray, during the filming of The Taybor. According to the SFX clapperboard, the date was 28th May 1976.

The interviews were with Gerry Anderson (chain smoking in his office), Keith Wilson (sitting on a polystyrene rock in a planet set of New Adam New Eve), Brian Johnson (in the model room), Martin Landau (standing by his Rolls Royce outside the studio) and Barbara Bain (sitting in the wicker chair in her dressing room, waving her cigarette around as she talks).

Space: 1999 production logo in Pinewood Studios. This is probably the balcony over the main entrance to the administration block. The photo was taken by William Anders on Apollo 8 orbiting 110 km above the dark side of the Moon on December 24, 1968.

Filming New Adam, New Eve, June 2nd or 3rd 1976. Top left is cameraman Neil Binney, behind assistant director Ken Baker (in red shirt). In foreground with glasses is director Charles Crichton. Behind the camera wearing a tank top is focus puller Mike Tomlin, with grip Michael Beauchamp (with beard).

The short woman is wardrobe assistant Elvira Angelinetta. The woman in foreground right is hairdresser Jeanette Freeman (we see her tending Barbara's hair in this sequence).

Gerry Anderson is sat at the desk in his office. Both Gerry and the interviewer, Munro, are smoking cigarettes (as do many of the cast and crew)

Q: Gerry Anderson, you're currently making the second season of Space: 1999. What inspired the creation of the first?

GA: Well, I think the answer would be long and complicated, but, briefly, when you're making pictures for commercial television, you're not free to make precisely what you want. We had made a series called UFO. This series had been very successful in the States, and we were asked to produce a second series of UFO. But unfortunately after 17 weeks of fantastic ratings, for some reason or other, suddenly, the ratings collapsed and there was to be no repeat. We had already carried out a lot of work to prepare for the second series of UFO and it seemed to be a shame to waste this. And so we adapted what we had already prepared, and adapted it further, until we suddenly found we had a new series, and this was called Space: 1999.

Bain is interviewed in her dressing room, sitting in her wicker chair and smoking. She wears a wrist watch over her uniform sleeve.

Q: Barbara Bain, how did you react when you were first offered the part of Doctor Helena Russell?

BB: Well, it was a kind of interesting experience all around, because Gerry and Sylvia Anderson had come over to the States with a gentleman named Abe Mandell from ATV to see Martin and I about doing it. We didn't know any of them. They arrived at our doorstep one day, they came in and presented the concept to us. They had a lot of sketches and a lot of story outlines, and a fantastic amount of enthusiasm. It was August in 1973. The more we talked, the more excited about it we all got. We were concerned about ... The whole concept of the show was appealing to us. Everything about it. We were concerned a little bit in the area of production. Science fiction is a difficult medium to produce well. It's a literary medium primarily, you can write something down in four or five words and the person who reads the book can make up anything they want to in their head. When you go to film it, you're going to disappoint, if you don't have either the imagination or the budget, and they had that as well. So we got very excited.

Q: Do you ever feel overwhelmed by the special effects?

BB: No, because were they not splendid and super, it wouldn't be very good. So we're very glad they are done as beautifully done as they are. Then our end has to at least match that.

Q: Why have you tended to concentrate on television?

BB: Well, a lot of reasons, first I came up in television. I happen to love it, absolutely love it.

Q: Why?

BB: Because of the extraordinary audience. There's just no way other than television today to reach as many people. Al Jolson in his whole lifetime never reached as many people.

Q: Working in television you've done a lot of episodes. Has the possibly ever occurred to you that you might become typecast?

BB: Well, I don't know if I'm typecast or not. I don't feel burdened by it one way or the other. However if I'm being typecast by them that typecast people I don't feel injured by it. I've been working, I've been lucky in the work that has come my way.

Q: What type of audience is Space 1999 aimed at?

BB: Well, that would be a question probably better put to the producers, but I don't think it's aimed at any audience. There's something of interest at all levels, because of the fantasy. Because of the ...um...relationship with one world with our current world... I don't think it's geared particularly for... I think there's something in it for everyone.

Landau is stood by his Rolls Royce, parked in front of the Pinewood administration block. The trees of Black Park are visible over the white fence behind him.

Q: Martin Landau, what sort of man is Commander Koenig?

ML: Let's start by saying he looks like me, and he's about my age. He was an astronaut, he was born in the 50s. He's really a product of today.

Q: Has he changed a lot since the last series?

ML: I think he has. I think he has much more humanity, much more humour. I think the scripts allow for a lot more of that.

Q: Did you have any hesitation about playing the part a second time?

ML: No, because one of the things we discussed as we went along was the fleshing out of the people, and I feel that we have succeeded in that area. I think there are many more levels to the character now.

ML: Science fiction is generally a great literary form. Writers through their sentences create all kinds of worlds. Red skies and red water and incredible life forms. Radio has a marvellous way of allowing the mind to do that. Now if the special effects were in fact disappointing, I would be inclined to... the series wouldn't be very good.

ML: Unlike a contemporary show, you really don't know who your adversary is. We're coming up against new things constantly. Whereas a Kojak, or a cop on the New York streets pretty much knows what he's going to run up against, especially after 5 years. The unknown is a constant challenge and I think that elevates us.

Q: Of course you made nearly 80 episodes of Mission Impossible.

ML: That's right.

Q: Could you see yourself doing the same number for Space 1999?

ML: Well, I think whenever I enter any kind of project I want it to be successful. I turned down numbers of series after Mission Impossible. Countless, mainly because there was a sameness to them, they were virtually variations on Mr and Mrs North. Several of the series went on the air, some of them are still on the air, some of them are off the air, but they didn't really ... present a kind of challenge that I like and also didn't interest me on the level that... uh... Doing a series is like being married, it's a day in, day out thing, and you have to kind of love it. Or love the idea of it.

Keith Wilson sits on a rock on the planet surface set of New Adam New Eve.

Q: What criteria do you bear in mind when you design a set like this?

KW: Well, obviously I have to read the script first. A set of this nature I have to plan the areas the main action is going to take place. It may look quite big, it's quite a small stage. To accommodate an entire film on this one set, I have to work out groups of action. Then we move the rocks round, and all the grass and the trees. And very quickly you can make it look like another part of the planet.

Q: Is all the vegetation artificial?

KW: No, our trees are real, the grass is real, but all the flowers, things like that, they're all plastic.

Q: Does it pose any problems having live vegetation?

KW: Well, we have to water it every day. On a feature film we would probably have to replace it every few days. Because it's for television, the picture ends up about that big (hands about 12 inches apart), we can get away with a lot that the big screen can't. These trees have been here about a week or so, and they'll last until the end.

Q: These rocks that we're sitting on, what are they made of?

KW: They're basically polystyrene, we just cover them with a very thin coating of plaster to give us the texture we want. But basically polystyrene.

Q: This is an Earth-like set we're sitting on. You also design all the other sets including sets of an alien planet. How do you set about designing the set of an alien planet?

KW: Again you read the script. I try and make as different as I can each time. Really it is down to me. Nobody can say that I'm right or wrong. The majority of times people accept what I do. We've had a couple of occasions when I've designed a set that was totally way out, that you just couldn't accept it. The general public just couldn't accept it.

Q: Why not?

KW: You have to have things that people can associate with. Here we have normal trees and automatically people say it's a planet surface, or Earth or whatever. We did things with huge balloons, and I said they were trees. But that was a particular case that didn't work. It looked very good, it looked very arty, artistic, but we're dealing with thousands of people, children, mums, dads, who just come home from work. They kind of sit there and scratch their heads and say 'that's a planet surface?' They've got to be told immediately. You can't go too far. You've got to know when to stop.

Q: What about the time problem? How long does it take to build a set like this?

KW: Well, we're doing a show every 9 days. People who don't know about film will say 9 days seems like a long time. It isn't. We have to do an hour's shooting in that time. While we are shooting that episode, I have to be getting all the sets ready for the next episode. I knew I would have two stages. I'd have one stage for planet surfaces, and one stage I had to concentrate all the Alphan sets. Now, no way would I have time or room to keep on building different sets every week. So I spoke to the producer Gerry Anderson and we had the idea of making a modular system. So it's like a big jigsaw puzzle. Every week I could change all the sets, very quickly because everything's a standard size. I used different materials on the surface of the flats, so that they wouldn't wear. The ones we've been using have been standing there for 3 years and we haven't touched them. Normally after every few weeks you would have to repaint. In this particular case we don't have to, they look as good as when the day we built them. We covered the entire stage with a vinyl cushion flooring. Normally you'd use Hessian, paper, paint, varnish, and again every few weeks you'd have to replace it. That flooring is as good as the day we put it down.

A nice panorama showing the background painting for All That Glisters. This would have been left over since March, until May or even June when this was filmed (other episodes had been on location, or used Alpha sets, and an alien landscape had not been required). A rock wall is created, possibly a cave wall for Mark of Archanon or New Adam, New Eve.

Q: You also designed the costumes. How did you come up with that simple but very effective design?

KW: Again, it's all to do with a modular way of living. We assume that these people are in a controlled environment. They wouldn't have a great deal of resources. So everything would be made from one cloth. This is the basis of our thinking. So the idea was to make this as simple and clean and clinical as possible, and easy to wear as it possibly would be.

Q: You also designed the commlock which the people carry on their belts. How do they actually work, in the series?

KW: In the series it's meant to be a total communication... They do have possibly the smallest television set in the world in them, one of them, we have a lot of dummy ones. The idea is that they open doors, they can talk, identification, everything on that one unit. Everyone has one. The story goes that, they are all programmed, so not everyone can go into every door. Only your particular commlock is programmed to allow you to certain areas on moonbase.

Filming from the side of the Medical Centre set for Mark of Archanon scene 26. Etrec is on the bed, with Helena and Alan. Charles Crichton is directing. This is a rehearsal. Nick Tate is not wearing the red jacket he will wear in the filmed shot.

Nick Tate: See that, Doc? The only problem with this kid is he hasn't had a square meal in the last thousand years. ... they're a little bit mixed up with a bit of hydroponic soya but still pretty good .... let's go

Charles Crichton stops them. Nick snaps his fingers and tries the line again- "Ah, sorry, hydroponic soya, little mixed up with hydroponic soya, but it's still good - is it?" Michael Gallagher: "But it tastes like the real thing." Nick: "But it tastes like the real thing. Is that ok, Doc?"

Charles Crichton to Barbara: You're actually on the moon when you say it.

Barbara Bain: I can go away and come back... No, no, you're right.

Raul Newney (Dr Nunez) watches on the far left, John Standing as Pasc watches on the distant right, behind the camera lens. The red-shirted man is camera operator Tony White. Just to the right of him, in a brown jacket, is director Charles Crichton

The hands on the left are director Charles Crichton. Barbara Bain stands next to assistant director Robert Lynn.

SFX assistant Dave Watkins attaches the top boosters to a striped Eagle (Eagle 1). Note the boosters are attached to the front half of the Eagle spine, not the back half as in The Metamorph. Watkins fires the engines using the freon gas canister in his hand. In many Year 1 episodes, the rear rockets had been painted black inside, and baffles were fitted. For the freon gas effect, the engines were reworked (with extra pipework visible on the exterior), and the inside of the rockets was shiny aluminium, without baffles.

Behind Watkins we can see various SFX models on shelves. We can also see, in front of the shelves but barely visible, the Main Mission tower, on it's side.

These are the shelves on the right. The 44 inch Eagle (Eagle 1) that Watkins had on the bench is now on the bottom shelf, still with the red striped pod.

Above it on the middle shelf is another 44 inch Eagle (Eagle 2) with a 44 inch booster pod.

On the top shelf is the large Ultra Probe. Hidden behind it is the smaller Ultra Probe, and on the left is an Into Infinity satellite, which is also seen in the graveyard in The Metamorph

The large remote controlled moonbuggy

This is a different Eagle to one that Dave Watkins was demonstrating. This is Eagle 3 (without a red striped pod). Alongside is the 22 inch Eagle and the crude second 11 inch Eagle, missing a foot pad.

The Main Mission tower model is more visible behind. On the floor you can just make out Taybor's gun and the Archanon ship.

When Brian Johnson is interviewed, the two sizes of Hawk from War Games

Q: Brian Johnson, you are the designer and director of the special effects here. You designed and built these models. Were you inspired by any other models previously?

BJ: No, I really couldn't allow that to happen because we have a format to work to, and models have to be designed around that format. One really can't say other than you use your experience on previous films and tv series. Every model has to be original.

Q: I notice that they're somewhat insect like, is that intentional?

BJ: Yes, very much so. It's a well known fact that anything mechanical that captures people's eye, I think anyway, like Concorde or devices like that, are very insect like. And so to make this really believable, I made this insect like as well. Not that I wanted to make it like Concorde. It was made rather like a grasshopper, and it leaps about all over the moon surface.

Q: Why do you need models of different sizes?

BJ: Depends on the shot that's required. If it's a long shot or a medium shot. We don't have very much space. We can't place the 44 inch model 200 feet away. So we have to use an 11 inch model, the same sort of distance as the 44 inch mode. And therefore, it then looks 4 times as far away.

A: What are these models made out of?

BJ: Perspex, fibreglass, brass tubing, steel tubing, turned aluminium jet motors. A number of different things.

Q: How does Pinewood communicate to you what sort of shots are required?

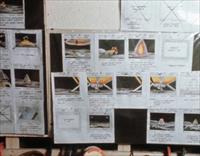

BJ: Well, the script is produced, and in its first stage I then have a look at it and say whether I think the effects are possible or make suggestions which hopefully will make it easier to do. Then it's rewritten. And from my point of view, we then go ahead and build the models and get ready for when it comes up. And we storyboard every shot. We storyboard them with little annotations which give us the scene number and the special effects slate number, so at the cutting room stage everything is very carefully put in little rolls so that it can be found again. It has to be said that with special effects shooting sometimes 3, 4 ,5 weeks behind the main unit, and sometimes in front, it's very easy for things to get lost.

Q: When the model explodes, do you actually blow it up?

BJ: No we don't. What we do is get the model to arrive in a predetermined position, and then we cut the film, and then we line up an explosion in the same position. And then we turn over again, and the two are jump cut together. And providing you've got enough pieces which simulate the shape of the model, spinning through space, nobody really realises that we haven't got it up.

On the left is SFX director Nick Allder, on the right Terry Schubert. The base of Taybor's ship is a much larger model than the main SFX model. The figure is a bendy rubber "Major Matt" figure from Mattel, about 6 inches tall. While it is painted orange with a yellow helmet, there is no backpack.

Terry Schubert, and Alan Barnard arrange the mountains behind the Taybor spaceship. Note that some mountains, and Moonbase Alpha itself, are flat photographic cut-outs, mounted on wood, while polystyrene rocks are placed closer to the camera. Terry is called "Terry Shoes" by Nick Allder at one point (there is another Terry on the SFX crew, Terry Reed). Cyril Forster is seen at once point.

NA: Can we take the buggy in closer? ... Yeh, what if the buggy was there, David? ... That's pretty good that.

NA: Just the very back cut out, the high one, is it free or on its own? Right, now take it to Terry Shoes... leaving the foreground one there. That's it, keep going... a little bit more, you've done it. There. Ah, now, sorry. Just come back a fraction, Terry. Whow. That's good. Now, your pole, Terry, if you could put that support pole right at the very end, we've done it. Now.

TS: How about now?

NA: That's good. Now, there's only one other thing we want. We want another rock. You see that one we've already got in there, that high one in foreground.

TS: Yes.

NA: Where that flat pancake-looking thing is, that one, we want to move that bit up a bit, are you with me? With a higher piece there.

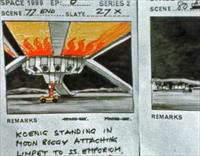

The SFX storyboard for The Taybor. Taybor's ship has the yellow and red base that was filmed, but the top cone looks grey in these storyboards. The following SFX footage is scene 77, and according to the clapperboard the date is 28 May 1976.

SFX director Nick Allder is talking to cameraman Dave Litchfield and lighting man Dick Lewis.

NA I think he's cracked it, don't you, Dave? ... Dick, can I have my single cam, mate? And I think we want to try it around about where that paint pot is. And we want to think about it with probably a double spun? in it.

DL: It doesn't look bad apart from that, does it?

NA Come round a bit more, cocker. That's it, that's it there, mate. Right, now flash it, sport. I think that's it, sport. ... Now Dick while you're there can you lift the lamp up a bit now. A little bit more. Right, now that's it, Dick. Put it on top of that.

Nick Allder and David Litchfield are in the camera pit with another man. They explain the camera grid system.

NA: What we have, this is an exact copy of what we put in the camera.

Man: It's the same squares.

NA: So an example of a shot we've already done, we had a planet, which we positioned there, so that's filled in, so we know we have all this out here that's unexposed. So then we flew an Eagle, that was taking that amount of film, that was travelling in that direction. So then we know we can't use that piece again. Then we rewound the film through the camera, we could move the Eagle, the same Eagle, doing that, again here, so we went round, building up, so we had 11 Eagles, all around the frame. So then we had to rewind, and then inbetween all these craft we had to fit in stars, around there, also doing it in such as way as you don't make a pattern that makes it look like clear little freeways down there. So just keep them to those little areas. That's 13 exposures in all, so it went through the camera 26 times, with perfect register.

Man: It's quite a precision job.

NA: It is. Something like that can take us the better part of most of the day. It's 30 feet of film.

Man: How long is that on the screen then?

NA: After the editor's got to it, it could be 10 seconds or it could be a 5 second cut. They're usually very kind to us, and might use the first part of it, cut away and cut back so they use the same shot twice, really. They help us there.

Q: You're a very patient man, I can see that.

NA: We have to be, sometimes.

Space: 1999 copyright ITV Studios Global Entertainment